Flitting around Europe to report on art events this Fall threw up evening opportunities to enjoy opera on either side of what was once the Iron Curtain. It still, in a way, remains: the stagings I saw in Budapest (Traviata) and Moscow (Queen of Spades) were radically different from those in Lausanne (Lakmé) and West Berlin (Tsar's Bride).

The Budapest Opera House (top left) opened in 1884 and Gustav Mahler, no less, became Director just four years later. Its unspoilt grandeur captures the spirit of the Habsburg Empire more than the celebrated Vienna Opera with its blandly rebuilt post-war auditorium. Budapest's style even extends to the brass-lamped cloakrooms and chandeliered buffet, where a full range of Tokays, from dry to super-sweet 5 Puttonyos, can be sipped amidst red-velveted splendor.

Verdi's Traviata tale of a high-class prostitute, based on Alexandre Dumas's La Dame aux Camélias, caused a furore when it premiered at the Opéra Comique in Paris in 1853. Klara Kolonits made a compelling Violetta in Budapest -- albeit more at ease flouncing around as a coquette, in a scintillating first act, than dying later on. Szabolcs Brickner, as her lover, Alfredo, was suitably uptight, and Anatoly Fokanov, as Alfredo's father, Germont, was suitably stolid.

The staging, in a 1997 version by András Békés, was a visual delight, conjuring up the decadent glamour of France's Second Empire with decor and costumes so sumptuously traditional, they could have dated from Traviata's first Budapest outing in 1857. Adam Medveczky conducted with sonorous relish before ambling uncertainly up on to the stage like an aging Homer Simpson caught in the footlights.

The Budapest Opera is said to be badly underfunded but, if this means retaining such "old fashioned" stagings, long may its financial woes continue.

The finances don't look much rosier at the Lausanne Opera. Or, rather, they look all-too-rosy: The auditorium (top right) is drenched in such a nasty scarlet that the audience needs sunglasses before lights down. Meanwhile, the basement bar looks more suited to a Friday-night student party than the clinking of champagne glasses between bejeweled Swiss Sunday fingers.

The cash-strapped aesthetics extended to the recent staging of Delibes's Lakmé, wherein a pile of mud straddled the stage as a riverbank, and a pile of metalware evoked a Hindu temple with a gleaming ingenuity Subodh Gupta might not have disowned.

Lakmé was premiered in Paris in 1883, at the height of Anglo-French colonial rivalry, and Delibes patriotically lampoons the British as cardboard cut-outs -- admirably (one fears unintentionally) embodied here by Christophe Berry as a lovelorn Gerald, gormlessly pursuing Julia Bauer's twittering take on a doe-eyed Indian maid. Lending gravitas to this mellifluous nonsense -- in fact taking the show by the scruff of the neck -- was St. Petersburg-born Daniel Golosov, who effortlessly navigated the bass-cum-baritone acrobatics of the priest, Nilakantha, spluttering fire and brimstone with the straggle-bearded conviction of an angry ayatollah.

From Sparta to Oligarchia. The Moscow Bolshoi re-opened in 2011, after a scandalously protracted, 1 billion dollars, six-year renovation (designed primarily to fill the pockets of ex-Mayor Yuri Luzhkov and his cronies), and now drips with con-fraternal acid, as well as enough gilt to bury a Las Vegas casino. Prices are so astronomic, that few Russian opera-lovers can afford tickets.

Still, Tchaikovsky's Queen of Spades in Moscow... Russian Opera at the Bolshoi... What could be better?

Russian Opera at the Mariinsky (where Queen of Spades was first performed in 1890), for a start.

Having, on my first visit to the Bolshoi, found myself next to a gum-chewing American in a back-to-front baseball cap, moaning about the lack of popcorn, I shed few tears when I learnt that Valery Fokin's 2007 version of Queen of Spades was in fact being performed at the Novaya Szena -- the Bolshoi's soulless, but less pretentious, second venue -- across the street (opened in 2002).

It was the Bolshoi's 1,278th go at Queen of Spades, a Pushkin short story set in 1796 St. Petersburg that relates how Herman, a gambling army officer, scares an aging Countess into vouchsafing the secret of a supposedly infallible three-card trick, frightening her to death in the process.

Roman Muravitsky was a bland, warbling Herman and Elena Zelenskaya as Lisa -- the sultry siren he woos to gain access to her Countess of a grandmother -- about as seductive as Marge Simpson. Much of the drama hinges on the physical frailty of the aging Countess, but she was played by Tatiana Erastova with disconcerting bluebottle verve. A balcony extended the width of the stage, reminiscent of Alexander Deineka's epic 1927 painting The Defense of Petrograd; the orchestra underneath, conducted by Vasily Sinaysky, was in finer form than the vocalists. This performance did not match the Queen of Spades I saw in Budapest in 2011.

Staging Russian opera outside Russia can, however, be a gamble. Rimsky-Korsakov's Tsar's Bride, as performed by the German Staatsoper at the Schiller Theater in Berlin, had too many tricks up its sleeve for its own good.

The action takes place in the 16th century Russia of Ivan the Terrible. The Tsar chooses a young bride, Marfa, whom his henchman Gryaznoy is coincidentally lusting after and, after a poisonous mix-up, the bride gets killed and Gryaznoy gets arrested. Under the staging of Dmitry Chernyakov, who transformed Marfa's home into a DDR apartment, and the Tsar's court into a TV studio littered with computer-screens, this convoluted plot -- with its now-ludicrous references to tsars and boyars -- was rendered utterly incomprehensible. It ended with Gryaznoy not arrested, but shooting himself in a swivel chair, which he simultaneously span around like a pirouetting figure-skater seeking Olympic gold.

Puerile melodrama notwithstanding, Chernyakov's Tsar's Bride was comfortably out-umphed by Stein Winge's Frankfurt version in 2006, where the malevolent mob -- the crucial Greek chorus to this dark, disturbing opera -- were allowed to roam the floorboards like predatory beasts, rather than be confined to the nooks and crannies of an artfully revolving, split-scene stage.

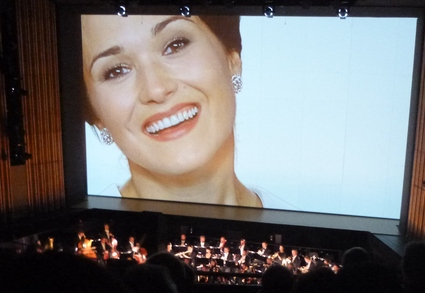

Daniel Barenboim's orchestra sounded suave, not Slav; baritone Johannes Martin Kränzle, as the pivotal Gryaznoy, strained to pronounce his Russian, and lacked vocal power. Olga Peretyatko exuded girlish charm as Marfa, but was subdued -- or perhaps intimidated -- by the overwhelming presence of Georgian mezzo-soprano Anita Rashvelishvili, who belted her way through the role of Lyubasha (Gryaznoy's longstanding lover) as if she needed to be heard back in the Caucasus, then milked the opening-night applause as if she, not Peretyatko, were top of the bill.

True, Peretyatko's face -- in Chernyakov's ultimate outburst of digital whiz-kiddery -- had just smothered the closing curtain with a big sister assertiveness fit to make a fellow-diva foam with envy. The sneaky Chernyakov, however, had not told Peretyatko what he was up to; nor had he informed her that the entire orchestra would materialize for a curtain call on-stage -- leaving Peretyatko, after taking her bow, to gesture towards an embarrassingly empty pit.

Rumors that Chernyakov threw a tantrum during rehearsals, accusing Peretyatko of hogging the media limelight, may or may not be coincidental.

Chernyakov is to opera what superstar curators are to the artworld.

Superfluous.

*

all photos © Simon Hewitt unless otherwise stated