With about 0.59 inches of rain a year the Atacama, high in the Andes Mountains of northern Chile, is the driest place on Earth, and very likely its oldest desert, going back 3 million years.

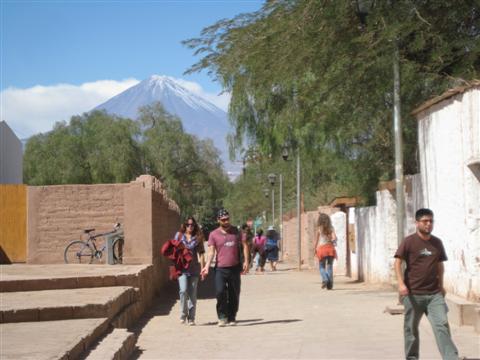

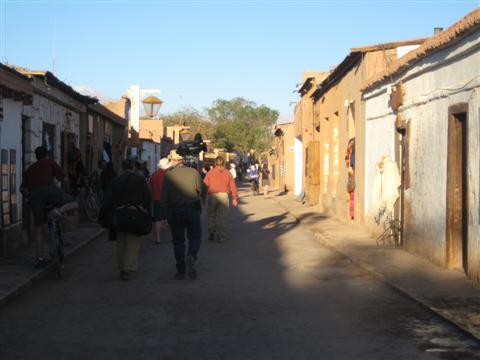

It is much more accessible than the Gobi or the Sahara. Roads and busses cross its 41,000 square miles, and the oasis village of San Pedro de Atacama, 8,000 feet up, has become a cutesy gateway to all the wonders of the high desert, reachable by plane or bus from Santiago, Chile's capital, its northernmost town of Arica, and major coastal centres in between.

San Pedro street scene

The scenery is superb. Snow-streaked volcanic peaks soaring up to nearly 20,000 feet wall off the desert to the east by the Bolivian border, and the height and dryness afford spectacular clarity.

The Atacama desert with its backdrop of volcanoes

On a night walk into town from my cheepie hostel on the outskirts of San Pedro, a blackout strikes, sending Yours Truly stumbling down embankments without the blindest idea of where I'm going. But at least it gives me the chance to admire the incredibly star-bright night sky without light pollution.

San Pedro de Atacama

Being a top place for astronomers due to its dry clarity, the world's largest radio-telescope nests among Atacama's peaks at the Llano de Chajnantor Observatory 30 miles to the east, seeking to reveal the mysteries of the universe. But I´m still having trouble trying to reveal the mysteries of Mother Earth, stumbling on blindly and getting nowhere near Caracoles, San Pedro´s main drag.

However the ancient mariners navigated by the stars, it´s not working for me. So I navigate instead by drunken party-goers in a nearby hovel who, beer in hand, point me, when they're not stumbling over each other, more or less in what, after several collisions with walls and undergrowth, turns out to be the right direction.

Tours are the best way to see the sites and sights unless you want to rent a 4X4 - and, if you're me, go off in the wrong direction. But as often with tours, the driver-guide speaks too much and takes us on long forays to souvenir shops where he gets a cut. A nine-hour trip would be just as good at six.

High mountain lake

We're six on the minibus - two Uruguayans, two Chileans, an Argentine and yours truly. They´re all pleasant, but I sound off on Chile's seizing a whole lot of Bolivian and Peruvian territory in the 1879 War of the Pacific, and now some of them have gone very silent. Will I never learn?

The sites are superb, among them the Quebrada de Jere oasis, a tiny valley, really just a narrow shallow break in the desert a few dozen feet wide and 20 or 30 feet deep, where underground water from the towering peaks produces a micro-climate with an uncanny sprouting of fruit trees.

Quebrada de Jere oasis

Patches of yellow tuft grass cover parts of the desert, and at 15,000 feet we reach two lakes surrounded by volcanoes. One is still active, smoking away gently. The whole scene is dominated by the snow-streaked cone of Licancabur, a dormant volcano 19,740 feet high.

Licancabur volcano

A huge salt flat with a corrugated surface hosts several lakes with pink flamingos. A little Andean fox, just like a puppy, stops to look at our minivan and poses when we get out. Evidently people have thrown him some food and he's lost his timidity, wanting more.

Salt flat

Salt flat lake

Flamingos

Andean fox

An ungodly wake-up at 3.30 a.m. will take you to El Tatio (the Granddaddy), one of the world´s highest geyser fields at 14,175 feet, which - damn it - is at its best at dawn, before the sun dissipates some of its steam. It's a phantasmagorical sight, steam and boiling water rising amid a moonscape of brown crags and snow-capped volcanoes.

El Tatio geyser field

Environmentalists worry that this otherworldly spectacle will disappear or be ruined since the giant energy-hungry copper mine of Chuquicamata 75 miles away wants to use the field for thermal energy.

It´s only 14 degrees Fahrenheit, but this doesn't stop the more idiotic among the tourist fauna from stripping off in the shivering cold, then plopping into the thermal pools. Needless to say, Yours Truly is not among them but a forefinger informs that the water is nice and cozy.

Columns of geyser steam

Of course, everybody's oohing, aahing and idiotically grinning as they jostle to get photos of themselves in front of the geysers and fumaroles, except again of course - you´ve guessed it - Yours Truly.

Sunrise over the geyser field

Unlike the Sahara, wildlife is much more evident - vizcachas, (a rabbit-type rodent with very pointed ears), vicuña (llama-like but smaller, wild and very graceful), ostrich-like ñandu, and domesticated llamas lording it over both pastures and tourists with undisguised disdain.

Vicuña in high desert

Vicuña

Browsing in high desert

We end up in Machuca, a typical little Atacameño Indian village with a quaint white-washed square church. Progress has reached even here; solar panels sprout from the straw roofs of the little stone houses.

Machuca church

Only one family still seems to live here - for the tourists. The lady's making cheese empanadas and the man's barbecuing llama meet.

Solar panels in age-old village

In the Cordillera de la Sal volcanic activity, water and erosion have teamed up over millions of years to create an arid wonderland of fantastic shapes, rugged forms, ridges and ravines from a mixture of clay, rock, minerals and salt, all baked hard by aeons of dryness - the so-called Valley of the Moon.

Valley of the Moon

One of its highlights is the narrow Valley of Death, with a profusion of ridges and soaring, tortured crags shining yellow in the sunlight, row after row of crenelated razor edges stretching out towards snow-capped Licancabur and his lower siblings.

Valley of death

Actually the name's a misnomer. An American archaeologist called it Valle de Martes (Mars) and some Chilean clown misheard it as Muertes (deaths).

Another valley of death view

And another

Chuquicamata, the largest open pit copper mine in the world, is where the young Ernesto Che Guevara had his Road-to-Damascus moment talking to two communist miners - the epiphany that set him off on his revolutionary path.

Being neither St. Paul nor St. Che, Yours Truly's having an off moment, mental constipation replacing divine or Marxist inspiration. Instead of the two miners of Che´s Motorcycle Diaries, my numbered seat by the window at the front of the double-deck bus from San Pedro to Calama has been stolen by a shrivelled old man - probably younger than me - with sunken eyes and an Andy Capp cap.

Sunset over Atacama towards Licancabur

As the aisle front window next to him is free, I don't make him move. He rewards me by falling asleep all over me, groaning every few minutes - hardly a fount for inspiration, divine or Marxist. From Calama group taxis go the dozen or so miles to Chuquicamata.

Copper miner's statue in Calama pays tribute to desert's wealth

The mine is enormous - over three miles long, 1.5 wide and 3,000 feet deep. A plume of dust rises over it in a straight column, bathing the whole arid ridge in haze. Vast slag heaps surround it. Chuquicamata itself is a ghost town now, its 20,000 inhabitants relocated for environmental reasons - and because there is profitable ore to be mined beneath the buildings.

Down into the jaws of hell - Chuquicamata's dust-smoking maw

It´s surreal to wander through the deserted grid of streets, past the large main square with its municipal building and the tiny squat row houses for the workers. On the other side are the mansions for their then gringo bosses.

I have one up on Che, though. I might not have a Road-to-Damascus epiphany, but I get into the mine, which is more than he did when he swung past in 1952. The then U.S. managers from Anaconda told him it was not a tourist site, so piss off.

Mountains of slag

Now, on carefully monitored tours by Codelco, the Chilean state company in charge since its nationalisation in 1971, you can gaze down into the deep maw gouged out of the arid rock, with ridge after ridge of mining operations descending in steps into the bowels of Mother Earth.

Gigantic trucks cart rocks upwards day and night, the largest trucks in the world with a 400-ton capacity and a cost of about $4 million each. The wheels alone, nearly 10 feet high, cost up to $30,000 apiece.

Gigantic ore carrying trucks

There are equally gigantic oohings and aahings from the 10 of us on the free tour and, of course, the frantic rush to have one´s photograph taken against the wheels - except for, of course, you´ve guessed it.

The next blog will take a look at the Sahara.