Here's a chilling thought for the Halloween season: If you're visiting one of New York's many amazing parks and squares, it's likely that you're standing on land that was formerly used as a cemetery or potter's field.

Manhattan is still dotted with several interesting historic cemeteries, such as the First Shearith Israel Graveyard at 55-57 St. James Place (pictured below, between 1870-1910). But a great many other burial grounds once existed but were removed due to new developments. And in several cases they even left the bodies behind!

In the colonial era, the city of New York was mostly confined to the area south of today's City Hall. As New York rapidly grew starting in the early 19th century, its population naturally moved up the island.

At the same time, deadly epidemics ravaged the city during various periods, forcing the city to quickly develop burial grounds and potter's fields (for unclaimed bodies) on the edge of town. But as what was considered "the edge of town" moved further north, those burial grounds were suddenly considered valuable land. In many cases, they exhumed the corpses and turned those spots into well-manicured public parks.

Sometimes, however, they left the bodies where they lay.

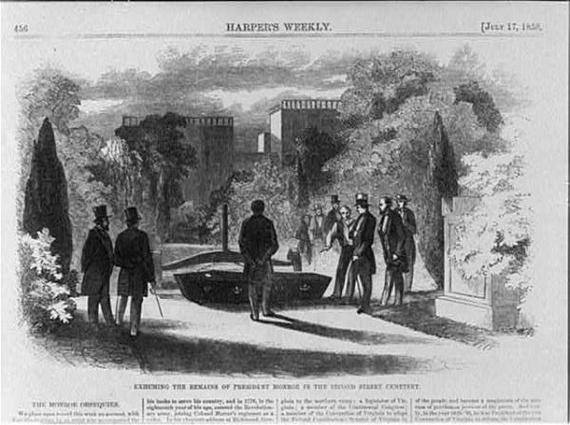

Above: In 1831, President James Monroe was buried at New York City Marble Cemetery on Second Street. His body was later moved. (Courtesy Harper's Weekly)

Most of these burial plots date from before 1851, when the city passed an ordinance forbidding further burials below 86th Street. Historical cemeteries (like those at Trinity Church and Old St. Patrick's) and land with private vaults (such as the East Village marble cemeteries) were allowed to remain, and unique exceptions have been made, such as the singular grave of William Jenkins Worth in front of the Flatiron Building.

Here's just a handful of Manhattan's old burial sites:

Liberty Place (at Maiden Lane)

Late 17th century -1820s

This burial ground served New York's first Quaker congregation and is sometimes referred to as the Little Green Street Burial Ground of the Society of Friends (Liberty Place, a tiny alley today, was once known as Little Green Street). Its location is near the New York Federal Reserve.

In the 1820s, the Quakers sold this property, exhumed their dead, and moved to a new burial ground at.....

Houston Street Burial Ground (105-107 East Houston Street)

Approx. 1820s-1848

This remained the principal cemetery for Quakers in New York during a period of incredible prosperity for New York City, thanks to the opening of Erie Canal and the planned formation of streets and avenue from the Commissioner's Plan of 1811.

Today this is the location of Whole Foods supermarket.

In 1848, the bodies were moved again to a private cemetery, where they remain today, located in today's Prospect Park. It was in this very cemetery in 1966 that the actor Montgomery Clift was laid to rest.

African Burial Ground

(Modern marker at Duane Street and Elk Street)

For almost one hundred years, starting in the 1690s, New York slaves and black freedmen alike were forced to bury their friends and loved ones outside the comfort of church and city limits, in an area south of Collect Pond, New York's source for fresh drinking water. As many as 20,000 bodies may have been interred here at one time.

It was a lonely and unprotected area; at one point, in 1788, bodies were even exhumed from here illegally for medical experiments. New York simply developed over the land in the 19th century, building department stores, government buildings, even opera houses.

For decades, the area's original identity went unmarked, until burials were discovered during excavations in the 1990s. A spectacular monument was built here on one portion of the former burial ground and dedicated in 2007.

For more information on the African Burial Ground, check out our podcast on the incredible history of this area.

Washington Square Park

1797-1825

"Where now are asphalt walks, flowers, fountains, the Washington arch, and aristocratic homes, the poor were once buried by the thousands in nameless graves." (Kings Handbook of New York, 1893)

This plot was used as a potter's field during a devastating outbreak of yellow fever. When fashionable New Yorkers moved from the confines of lower Manhattan to this area of Greenwich Village, the burial ground was closed for business and a lovely park placed on top of it.

While this might seem truly morbid, in fact the city considered this a preventative and sanitary option. According to city records, a recommendation was made that "the present burial ground might serve extremely well for plantations of grove and forest trees, and thereby, instead of remaining receptacles of putrefying matter and hot beds of miasmata, might be rendered useful and ornamental."

Of course, in modern times, that "hot bed of miasmata" serves as one of New York's most bustling and vibrant outdoor spaces. But the city simply built over the burial ground. It was claimed during the 19th century that a blue mist could be seen hanging over the park at night, the creepy vapor of the remains underground.

It is believed that over 20,000 people are still buried here. Bodies are routinely uncovered during excavations.

If you'd like more information on the history of Washington Square Park, you might like my audio walking tour, which takes you through the park and around its perimeter.

Image courtesy New York City Cemeteries Project

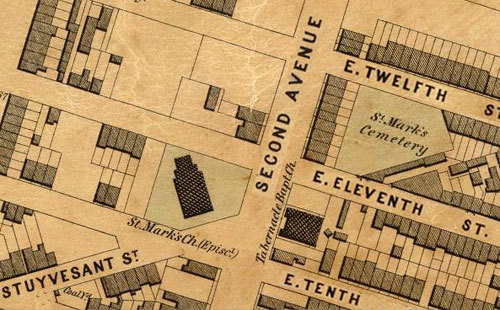

St. Marks Church-in-the Bowery - Second Burial Ground

1803-around 1851

One of the East Village's most historic landmarks, St. Marks Church-in-the-Bowery has a very famous burial area on its immediate land, strewn with the vault markers of famed families, as well as that of New Amsterdam director-general Peter Stuyvesant. But the congregation owned another burial ground one block north for less wealthy members of the community. Most notably, many stars of the theater were buried here, including Stephen Price, impresario of New York's famed Park Theater.

According to historian Mary French, the land was donated to the church by Peter Stuyvesant IV, with an unusual stipulation, " that any of his present or former slaves and their children have the right to be interred in the burial ground free of charge."

This yard was closed for several years before St Mark's finally sold it in 1864, and the bodies were moved to Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn and Queens.

Union Square

Probably late 1790s-1815

Potter's fields -- where the poor or unclaimed were buried -- moved frequently around the city as land values improved with the city's growth. This particular area at 14th Street was once comfortably outside of town, but its proximity near Bloomingdale Road (the future Broadway) soon required its functions as a burial plot be transferred to other usable fields, like Washington Square.

The land here was transformed into the elliptical-shaped Union Place, a strolling park surrounded by an iron fence. By the 1830s, Samuel Ruggles would modify it further into New York's toniest park, Union Square, luring the wealthy who quickly built homes of 'costly magnificence' around it.

For more on the history of Union Square, check out our podcast history on this fascinating park.

Madison Square Park

1794-1797

The short duration of this burial ground stems from the fact that it was used only to inter those who died at nearby at the hospital at nearby Belle Vue Farm (today's Bellevue Hospital) and the local almshouse during a devastating yellow fever epidemic. Later, with fears of a new war with England looming, the land was given to the U.S. Army as an arsenal, and the land that was later Washington Square became the official place to bury the dead.

There's some evidence to suggest that some of the remains were never moved.

Bryant Park

1823-40 but possibly used as late as 1847

Yet another burial plot for paupers, still further north of city center. Soon however the adjoining land became an ideal spot to put the Croton Reservoir, supplying the city with drinking water. And, well, it wouldn't do to have a bunch of graves next to that, would it? After a duration as the location of the grand Crystal Palace Exposition, the land was turned into a park, named after editor William Cullen Bryant.

While it's unclear whether the old potter's field grants the park any kind of supernatural aura, the New York Public Library (on the site of the old Reservoir) provides some of the more interesting specters from the film Ghostbusters.

Park Avenue and 49th Street

1822-1859

In the early 18th century, the area soon to become known as Park Avenue, the richest street in America, was home to railroad tracks, cattle yards, various grim asylums and, yes, Manhattan's last potter's field.

Before Columbia University moved to Washington Heights, it was located here in this area of today's Midtown. The campus sat near this unpleasant spot, a potter's field so shockingly maintained that "the ends of coffins still protruded from the ground," according to historian Edward Sandford Martin, "a malodorous neighbor much in evidence and disrepute."

In the late 1850s, the city forced the potter's field off the island entirely, and the bodies were slated for removal to Ward's Island (today attached to Randall's Island). Given municipal corruption and delays, however, the project took years, with train passengers often greeted with the sight of coffin stacks and grisly open pits.

Today, that former burial plot is occupied by the Waldorf=Astoria Hotel, built on the property in 1931, long since transformed by the burial of tracks into Grand Central Terminal.

NOTE: Some of the dates above are estimates, as record keeping for these kinds of things is rather hit and miss! Many dates are from Carolee Inskeep's exhaustive survey of old New York burial grounds The Graveyard Shift.

And if you're in a Halloween mood, visit our blog and download our latest Halloween-themed podcast, Early Ghost Stories of Old New York!