Body fat: It's soft, it's squishy and it gets a bad rap. But fat also plays a vital role in keeping our bodies running smoothly. We store extra energy in body fat. It keeps us warm and provides padding for our interior organs. And it secretes chemicals that play a role in appetite and helps regulate menstrual cycles, among other functions.

In other words, in healthy amounts, it's a wonder organ -- but people don't seem to be very interested in fat except for how to lose it. Read on for some of fat's amazing abilities, as well as tips on how to treat it right.

1. Fat has different colors.

When you think of fat, you most likely think of the white stuff on your tummy, hips and thighs that stores energy until you need it. But there's also brown fat, more prevalent in newborns because it helps them keep their body temperatures stable without shivering. It turns out adults have small amounts of brown fat too, although a lot of research still needs to be done to determine exactly what role it plays.

In 2012, scientists at the University of Sherbrooke published a study showing that when study participants, all men, were exposed to cold temperatures, the brown fat in their bodies kept them warm by using white fat as fuel. In other words, the brown fat burned up the white fat for energy and warmth.

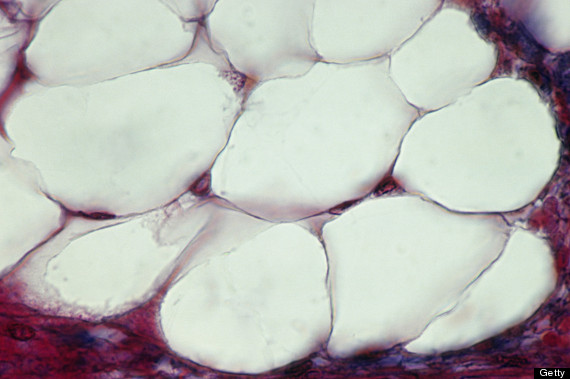

A close-up of fat cells shows the nucleus and cytoplasm pushed to the edges to make room for the fat droplet.

2. Not everybody has brown fat.

However, brown fat almost never shows up in obese people, notes the New York Times, which is why researchers are investigating if the lack of brown fat causes obesity or whether their extra white body fat prevents them from activating their brown fat.

Brown fat researcher Shingo Kajimura, Ph.D., of the UCSF Diabetes Center told HuffPost that adults have about 50 grams of brown fat that can burn energy equal to roughly 10 pounds of white fat a year. However, people start losing brown fat in their late 40s and early 50s, and he suspects this could be related to age-related obesity. Kajimura has been conducting brown fat trials on mice to see if he can activate or inhibit brown fat's growth, and in a yet-to-be published study, he explains that his team has found an inhibitor to stop the enzyme that helps brown fat grow. He is now looking for brown fat's activator, which he hopes can lead to a cure for obesity and obesity-related diseases like diabetes and hypertension.

The research is so preliminary that there are multiple points of view about the significance of brown fat; nutritional biochemist Shawn Talbott, Ph.D., told Shape.com that the amount of brown fat in humans is so small that we can't count it on it to burn calories or keep as warm. But Kajimura told HuffPost that a drug to stimulate brown fat's energy-burning properties is a "realistic future" if research continues.

3. Fat keeps us warm, and not just by insulating us.

All fat cells -- not just brown ones -- can sense temperature directly, and they respond to cold by releasing their energy as heat, according to a 2013 study reported on by ScienceNOW. The heating process depends on a protein called UCP1, explains ScienceNOW, and when researchers at Harvard Medical School exposed white, brown and "beige" (a mix of white and brown) samples of lab-grown human fat cells to cold temperatures, the amount of UCP1 proteins doubled in white and beige cells.

"Now we know they can sense temperature directly," lead researcher Bruce Spiegelman, a cell biologist at Harvard Medical School, told the publication. "The next question is, how do they do it, and can that ability be manipulated?"

4. Exercise could change the behavior of your fat cells' DNA.

The amount of fat your body carries is partly determined by genetics, but researchers at the Lund University Diabetes Centre in Sweden found that exercise could play a role in switching on or off certain genes that have to do with fat storage, reports the New York Times. Researchers sucked fat cells out of dozens of sedentary but healthy Swedish men and then subjected them to a six-month regimen of spinning or aerobics classes twice a week. At the end of the six months, the men had dropped weight and were healthier. But many of the genes in their fat cells had also been altered, some having to do with fat storage and the risks for developing obesity or diabetes, the Times reported.

5. Not all fat cells are created equal.

Some obese people are metabolically healthy, while others have metabolic diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels -- and it turns out you can see the difference on a cellular level. A new study in the journal Diabetologia suggested that the fat cells of unhealthy obese people look and act differently than the fat cells of healthy obese people. Instead of making new cells to store more fat, the original fat cells in unhealthy obese people just swell to their breaking point, the New York Times reports, which leads to inflammation and fat storage on organs like the liver and heart. The fat cells in healthy obese people, however, are smaller and make new fat cells when more fat needs to be stored.

"It does paint the picture that there are two kinds of obesity, but so far we've been treating everybody the same and evaluating people's risks as the same. And that absolutely needs to be rethought," Jussi Naukkarinen, M.D., Ph.D, a research scientist at the University of Helsinki who was part of the study, told HuffPost.

Obese people are commonly told that they're at risk of developing metabolic diseases, but perhaps it would be more effective to target those who actually have unhealthy fat cells, he said. However, Naukkarinen pointed out, just because an obese person is metabolically healthy, it doesn't mean that he or she will stay that way forever. Currently, he and his team are continuing to research the way different fat cell sizes relate to various metabolic outcomes.

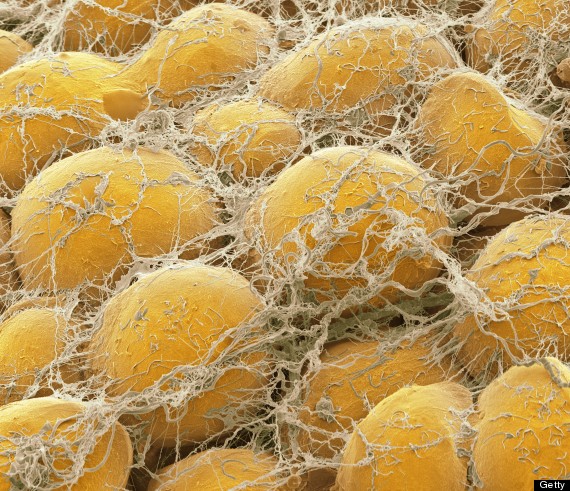

A close-up of fat cells from a scanning electron microscope.

6. Human body fat is full of potential stem cells...

And those stem cells are similar to the ones derived from embryos. In 2009, researchers at Stanford's School Of Medicine found that human fat removed during liposuction contained versatile cells that could be coaxed into becoming pluripotent stem cells, or cells that can become fat, bone or muscle. The process was easier than converting skin cells into stem cells, which is what researchers use most often.

“Imagine if we could isolate fat cells from a patient with some type of congenital cardiac disease,” study author Joseph Wu, M.D., Ph.D., of Stanford's Cardiovascular Institute, said in a statement about the finding. “We could then differentiate them into cardiac cells, study how they respond to different drugs or stimuli and see how they compare to normal cells. This would be a great advance.”

7. Fat cells need sleep, too.

If you skimp on sleep, you might be hurting your body fat's ability to respond to insulin, which could lead to weight gain or diabetes down the road. Researchers with the University of Chicago Medicine recruited seven young, lean and healthy people to participate in the study. The first week, they spent 8.5 hours in bed for four consecutive nights. One month later, they spent just 4.5 hours in bed for four consecutive nights. During both sleep sessions, food intake was identical.

At the end of each four-day period, the researchers removed fat cells from the volunteers' abdomens to measure how they responded to insulin. After four nights of short sleeping sessions, the fat cells' insulin sensitivity had decreased by 30 percent -- comparable to the difference between obese vs. lean people, or people with diabetes vs. people without diabetes. The results were published in a 2012 study.

8. Doctors are more concerned about the fat you can't see.

Love handles, flabby forearms and double-chins; while these visible (and grab-able) signs of excess fat can be troubling, it's the visceral fat, or fat you can't see, that should be of more concern.

Fat right under the skin, or subcutaneous fat, acts as our insulator and cushion in addition to an energy storage unit. But visceral fat, which is embedded deep within the abdomen, fills in the spaces between our organs and pumps out chemicals that can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes, according to Harvard Medical School.

If you're a pear shape, most of your fat is subcutaneous. But if you're an apple shape, a larger portion of your fat is visceral. Luckily, visceral fat, like subcutaneous fat, can be reduced by losing weight in a healthy way. Aerobics and strength training, along with a healthy diet, can help control weight and visceral fat. However, visceral fat does not respond to spot training, which means sit ups alone won't do the trick.

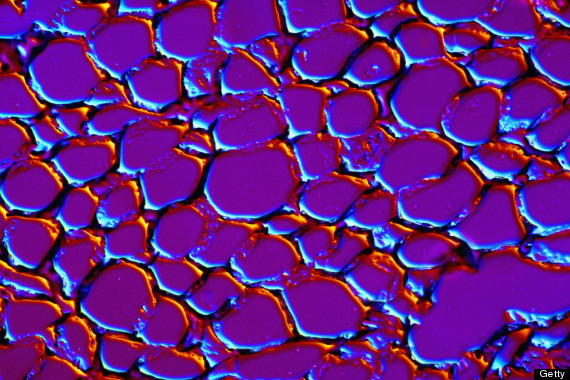

A close-up of adipose tissue (fat).