A while back, an environmental science and photography student from NYU named Madeline Cottingham, who is also a vegan, came out to my pasture-based pig farm to work on a farm to table photography project. In addition to seeing my farm, we planned to visit my local slaughterhouse.

After a tour of the farm, we had about half an hour before it was time to leave for the slaughterhouse, so we went inside for a cup of coffee, during which I brought up the fact that she is a vegan, and questioned why she would choose a livestock farm for her project. Her answer was very reasonable and straightforward: If people are going to eat meat, the animals should be humanely raised and killed. In spite of the fact that she was a vegan herself, she was willing to admit that most people would continue to eat meat; she just hoped that the animals wouldn't come from factory farms and wouldn't be killed in industrial slaughterhouses.

After our cup of coffee, we hopped into her car and started off for the slaughterhouse, which is about twenty minutes from my place. On the way, I reiterated that I thought she would have fairly limited access to the kill floor. My expectation was that she would get to stand in the doorway and take pictures from there. However, much to my surprise, when we showed up and I introduced Maddy to the slaughterman running the kill floor, he immediately invited her in. First she had to don a white coat and a hard hat, which she happily did. While I watched her get ready it seemed to me that she was almost giddy with the excitement of being given access to the whole kill floor.

There were only two rules on the kill floor: 1) One is not allowed to take pictures of the USDA inspector (a USDA rule) and 2) She was not allowed to take pictures of the act of stunning the animal or sticking it with the knife (a slaughterhouse rule, promulgated not out of a feeling that they have anything to hide, but out of a justified paranoia [I believe] of potentially being portrayed in a bad light).

As Maddy stepped past the threshold of the door onto the kill floor, I said, "Just let me know when you've had enough, and we'll go over to the cutting room." In order to keep the kill floor from getting crowded, I hung out in the doorway and watched from there.

For the next half hour or so, Maddy poured over the kill floor, snapping photos of everything, only pausing when the slaughterman brought a new pig onto the floor to kill. Rather than turn away for the killing, since she couldn't photograph it, she watched, intently, as the slaughterman placed the captive bolt gun against the pig's forehead and activated it.

BANG!, about as loud as a cap gun, and the pig dropped instantly to the ground each time. Then she watched just as intently as the slaughterman put down the captive bolt gun and pulled his knife out of the scabbard hanging off a white plastic chain wrapped around his waist, which he deftly and expertly plunged into the pig causing the blood to gush out in a huge stream. A moment later, which is why you have to act fast when killing pigs, the pig's death throes started, which, compared to other animals, are very violent. The pig, unconscious from the blow of the captive bolt gun, and quickly dying, and then already dead, thrashes around like mad. It is in fact the most difficult part of watching a pig killed because it is so easy to imagine that the pig is thrashing around because it is in pain (and, I grant the possibility, though remote, that we do not properly understand the physiology of death and the pig is in fact in pain, in which case what we are doing is very wrong). Nevertheless, as soon as the slaughterman pulled the knife out of the pig and stepped away, Maddy rushed in to start snapping photos again.

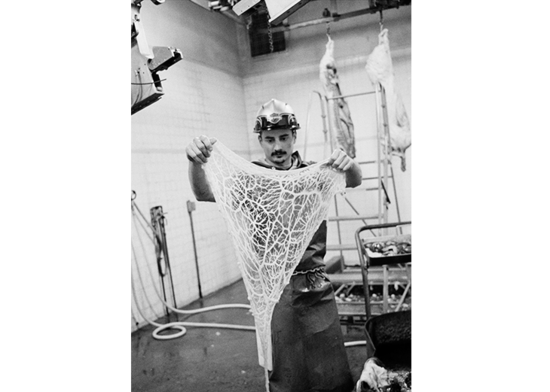

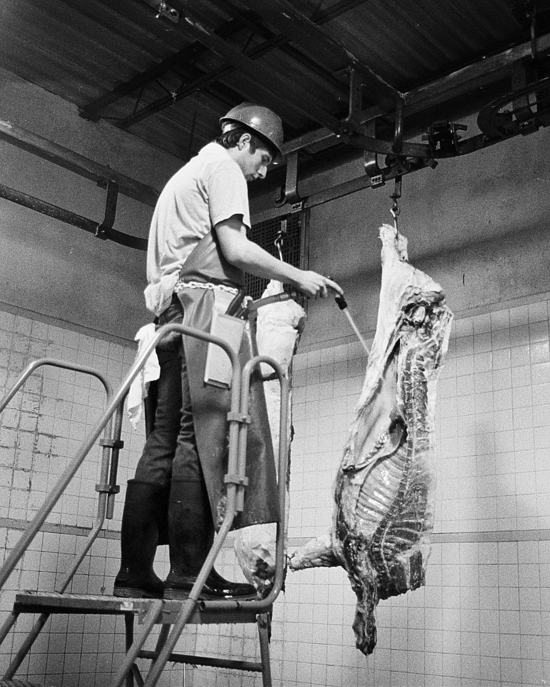

She took pictures of everything: of the moments immediately following the kill, of the pig being hoisted up by a hind leg to finish bleeding out and then be hosed off, of the pig being skinned, of the pig's head being cut off, of the pig being disemboweled, of the pig being split in half with a bone saw, and finally of the pig halves being run down the rail to the cooler.

The whole time, too, Maddy was aware that these were my pigs that were being killed. Not the very pigs that she had just seen alive and well on my farm, but the same pigs, nonetheless. They were not abstract pigs. They had faces and attitudes and personalities. They had lives that she had witnessed and documented just before seeing them killed.

I thought she would never tire of the kill floor. It seemed that everything attracted her. When not much was going on, she pointed her camera down at the floor and snapped pictures of spatters of blood and bits of skin and fat, the detritus of death.

Every now and then, however, she would look at me, and say, "just a few more minutes." Until finally she walked over to me and said, "OK. I'm ready."

The cutting room is a very different place than the kill floor. Everything is pretty familiar. As the carcasses come out of the cooler, they are quickly broken down into cuts that we are used to seeing in packages at the supermarket. Nevertheless, she snapped away, just as excitedly as she had on the kill floor.

After about a half an hour in the cutting room, we were ready to go. We said our thanks and left.

On the way back to my place we were pretty quiet, but at one point Maddy said thoughtfully, "You know, it wasn't that bad," which resonated with me because I had felt the same way the first time I watched my pigs be killed.

"Yeah," I said, "I know what you mean. My first time there, I expected that watching my pigs be killed would be very difficult, maybe even traumatic, but I was really surprised at how easy it was to watch. After thinking about it, I realized that the place, the whole place, everything about it, from the tile walls, to the white coats and hard hats, to the stainless steel hooks hanging in the air, to the chains and pulleys of the hoists, to the attitudes of the people working on the floor, is perfectly designed and organized to do that job and none other. Somehow that design and organization makes it so that on the kill floor, killing seems perfectly normal, natural, even. You don't even need to distance yourself from it. You can watch, you can stand there and say to yourself, okay, this is my pig, a pig that I cared for twice a day for five months, you can even recognize the pig -- oh, look, that's that pig that liked to have its belly scratched so much that it would topple over onto its side and lay there with its legs stretched out as soon as you started rubbing it -- and then BANG! and the pig drops and the wheels of the killing machine start rolling, so smoothly that it is difficult while it is going on to question whether it is right or wrong. From start to finish it seems exactly as it should be. Simply put, it just is. You know what I mean?" I turned my head to look at her while she was driving.

"Yeah," she said, nodding her head slowly while continuing to watch the road, "I think I do. It wasn't that bad," she said again.

A Message From Maddy:

"I grew up on a small, family run farm. I helped as we raised and cared for our animals, I helped when we killed them, and I helped to butcher and then eat them. Throughout my childhood I knew the names of the animals on my dinner plate. It was dramatic and sometimes troubling, but to me, there was nothing unique about this; it was what I knew.

That changed when I was eleven and learned about factory farms, which prompted my decision not to eat meat, let alone any animal products. I was suddenly disgusted by the entire process. I've been vegan for twelve years now.

There are numerous issues with our current food and meat production, but there are also alternatives. There are ways to produce and eat meat that don't harm the land, the animals, the farmers or their communities.

Documentary photography tends to depict the problems without an appeal for a solution. Photographing with Bob and in the slaughterhouse is an effort to portray this unconventional, yet sustainable food source. Being able to capture the entire process was an ineffable experience, which I felt incredibly lucky to capture on film."

Photo Credit: Madeline Cottingham

You can find more of Bob Comis' writing at stonybrookfarm.wordpress.com