Two years ago, Google launched its own version of Facebook, a social network dubbed Google+ that claimed it would fix the “broken” and “awkward” state of sharing online. Along with breathless descriptions of everything Google+ could do for us, there was a brief hint at what we could, in turn, do for Google+: “We want to make Google better by including you, your relationships and your interests,” the company wrote at the time.

Finally, we know what Google had in mind: It’ll be sticking us in its ads.

Google announced Friday that it will begin featuring users’ photos, names and comments in the promotions it serves up online, both on Google properties and on the more than 2 million sites that tap into its advertising network.

Ratings, reviews, relationships, comments, posts and other information taken from our activity on Google’s websites, such as Google+ and YouTube, will be repurposed and served up in these new so-called “shared endorsements.” For example, if you review Candy Crush or “+1” a steakhouse on Google+ (the equivalent of a Facebook “like”), your friends might see your picture and name show up alongside ads for that app or restaurant.

It’s clear why these personalized ads are better for Google and its paying customers. But it’s also clear that the rise of the friendorsement -- relationships repackaged as ads -- risks making our interactions online more awkward, not less. Google is taking advantage of our relationships and reputations to sweeten sponsors' pitches, transforming us into spokesmen in situations we don't always have control over. By making us into its salesforce, Google is transforming the soulmate into the sellmate.

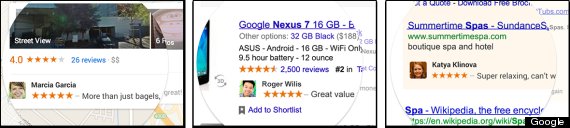

Examples of shared endorsements, via Google.Google is hardly the first company to try gussying up ads with our faces in an attempt to make promotions more palatable. In 2011, Facebook introduced “Sponsored Stories,” a controversial ad type that let brands use a fan’s name and photo when pitching to that person’s friends. The ad format brought in several hundred million dollars between 2011 and mid-2012 -- and a class-action suit that Facebook settled earlier this year. In August, Facebook tried again, updating its privacy policy in ways that would "allow Facebook to routinely use the images and names of Facebook users for commercial advertising without consent," privacy advocates alleged. The Federal Trade Commission is currently reviewing the proposed changes.

Examples of shared endorsements, via Google.Google is hardly the first company to try gussying up ads with our faces in an attempt to make promotions more palatable. In 2011, Facebook introduced “Sponsored Stories,” a controversial ad type that let brands use a fan’s name and photo when pitching to that person’s friends. The ad format brought in several hundred million dollars between 2011 and mid-2012 -- and a class-action suit that Facebook settled earlier this year. In August, Facebook tried again, updating its privacy policy in ways that would "allow Facebook to routinely use the images and names of Facebook users for commercial advertising without consent," privacy advocates alleged. The Federal Trade Commission is currently reviewing the proposed changes.

Unlike Facebook’s Sponsored Stories, which made participation mandatory, Google will allow its members to opt out of appearing in its digital billboards. (Find out how to do so here -- the changes will go live November 11.) Individuals who don’t explicitly revoke permission may have their likeness appear to “friends, family and others.” Users under 18 may see Google’s “shared endorsements,” but they will not appear in them. According to The New York Times, the update will affect not only the 190 million users who actively post on Google+, but also the "390 million [who] use the social network indirectly by sharing on other Google sites like YouTube," and potentially others who use Google's suite of services.

On the surface, it might not seem like such a bad idea to pair people with products in online ads. The advertisers get our attention. We get to hear what our neighbor/friend/cousin/estranged college boyfriend thinks of Brand X. The narcissists out there will also relish the additional visibility. (Google pitches the new ads as a way to “ensure that your recommendations reach the people you care about.”)

Yet in practice, the promotions aren’t always so useful. While these social networks know who we follow and friend, they’re still largely unaware of whom we trust. Given our expansive and eclectic collection of acquaintances online, we end up getting fashion suggestions from people we only trust for their nose for tech news, or restaurant recommendations from ex-roommates with abysmal taste. Just because we know someone online doesn’t mean we want -- or have any faith whatsoever in -- their opinion on what to buy.

In addition, the “+1” and “like” are watered-down terms that don't necessarily mean what tech firms assume they imply. We “like” things all the time we don’t really like, and the new ad format risks confusing an interest with an endorsement. Republicans will “like” or “+1” Obama’s page just to get his updates; friends will “like” an app because their friend asked them to. It’s awkward -- and just plain wrong -- when our names appear alongside products making it seem as if we endorse them.

But the biggest issue of all is what it may do to our relationships as we get used to seeing friends' smiling faces plastered next to mattress and hotel ads. When Google+ launched, Google criticized Facebook for devaluing the concept of "friend" with its one-size-fits-all categorization for acquaintances, colleagues and close friends. "[O]nline services turn friendship into fast food -- wrapping everyone in 'friend' paper," Google wrote in 2011. Only now, Google (and Facebook) are also morphing friendship into an efficient delivery mechanism for ads.

You can hope to be a good friend. But you'll definitely be a friendorsement.