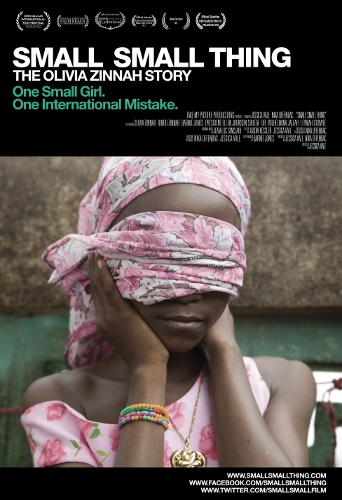

There is something about her eyes. Big, round saucers brimming with innocence that can see right through you. A dark scar runs down her cheek, a permanent tear for a girl who has a lot to cry about but instead smiles.

There is something about her eyes. Big, round saucers brimming with innocence that can see right through you. A dark scar runs down her cheek, a permanent tear for a girl who has a lot to cry about but instead smiles.

"She draws you in," said filmmaker Jessica Vale. "Her eyes pierce through your soul."In 2009, Vale went to Monrovia, Liberia to film a documentary on U.S. surgeons in post-war countries. When she was unable to film due to disclosure reasons, Vale found herself in a hospital with only the remnants of a story. Then, she met nine-year old Olivia.

Olivia Zinnah, a young girl who was raped when she was seven years old, is the subject of Vale's documentary "Small Small Thing."

"When I first met her she was in a really, really sad state, really malnourished. They had just given her the colostomy bag," Vale recalled.

Olivia was born and raised in Todee, Liberia, a small village outside the country's capital, Monrovia. Her mother, Bendu had kept her daughter in hiding for two years after she became ill, believing Olivia was cursed. A family friend convinced Bendu to take Olivia to the hospital, where doctors discovered that the child had internal injuries, the result of being raped two years prior by a cousin who was in his 20s.

After hearing Olivia's story Vale knew she had to take action. She headed back to New York where she utilized more than a decade worth of connections in the film industry for donated film equipment. She also contacted director, filmmaker and friend Nika Offenbac who jumped on board.

"As a film maker and as a professional freelancer," said Nika. "I had the time and resources to help put an end to what was going on by making people aware of it. Child rape was just not something I could sit by and let happen."

Back in Liberia, Vale and Offenbac shadow Olivia and her mother, Bendu for two months. Bendu was pressured by police to press charges against her cousin at the risk of losing her support system; her village. The taboo and stigma attached to rape left Bendu exiled and torn between two worlds.

"Before they see the film, a lot of people don't understand how a mother can be torn about this," she says "A lot of the film is devoted to Bendu's decision on whether or not to go back to her village or stay with Olivia. She doesn't have any education, she doesn't read or write. All she knows is how to farm and live with her family."

The documentary lends a voice to a side rarely heard in cases like these, the men. Due to decades of civil war, rape was the predominant method of intimidation demanded of child-soldiers. Now grown men, unemployed with little to no education or opportunities, they are left with haunting memories.

"The war stopped and then what? There really has been no education and no therapy," said Vale. "One of the guys in the film tells us that he has flashbacks on a regular basis and that he beats his wife. He doesn't have an outlet. I think that that's a large part of it."

Though her alleged rapist was arrested, he was released with hundreds of other rapists due to overcrowding and lack of evidence.One of the key people involved in unraveling the truth behind Olivia's story was Liberian, Barnie Jones who served as a translator, cultural bridge or as some say a "fixer." Jones lost her father, grandfather and uncle in the war. When she met Olivia in the Monrovia's JFK hospital she saw herself.

"I could've been Olivia," said Jones. "I was affected by the war but I always tell people I was very blessed."

When the Liberian administration heard about Olivia's case several surgeons were sent and different surgeries performed, despite previous advice to wait until she matured. Her case began to gain a lot of attention due to ties between the family friend that admitted Olivia and the Liberian administration. Young Olivia soon became a guinea pig.

"Olivia had way too many surgeries done on her, many of them were botched," said Vale. "We interviewed a lot of the Ministry of Gender, unfortunately it does come across that it wasn't the most coordinated effort."

After her last surgery resulted in a bowel obstruction, Olivia passed away at age 14. Vale was back in New York, working on the post-production of the film when she heard the news.

"It completely changed everything," she said. "Not only did we spend a few weeks trying to emotionally grasp what was going on we had to go back and change certain aspects of the film."

Now with an ending dedicated to Olivia, Vale plans on partnering with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like Holistic Education Advocating for Leadership (HEAL), founded by Liberian Mawata Kamara a foundation that aims to increase DNA technology in Liberia.

The UN presence in Liberia has been actively using Olivia's case to push for a new agenda about violence against women. However, Vale has found herself fact-checking both the UN and Liberian media when it comes to Olivia's story.

"I'm really happy they're taking it seriously enough to start presenting the story and the issues," she says. "But I want to see them do more."

The filmmakers demanded a statement from President Ellen Sirleaf Johnson, who was elected in 2006 promising her administration would empower Liberian women, however rape is still the number one crime, many of the victims being children. For months their request was unanswered.

Recently however, President Sirleaf launched the Anti-Rape campaign. According President Johnson, 60 percent of rape victims are children between ages 5 and 13.

In a statement at the campaign's launch President Johnson stated:

"Sadly, with all of these responses, with all of these mechanisms inplace, the heinous crime of rape continues to claim the lives of children- our country's future leaders. We listened to those kids. Let me cite afew: we lost Sarah Mulbah, age 8, on July 31, 2012; Comfort Maname, age13, on September 13, 2012; Massa Flomo, age 10; Olivia Zinneh Gbanjah who,in 2007, at age 7, was raped in Todee, by her Uncle Joseph Nupolu who wasnever arrested, and who finally died - may he go to hell - on December 18,2012"

Despite mistakenly listing Olivia's uncle as the culprit this is the first time President Johnson has made a statement in Olivia's behalf. Thus far, Small Small Thing has garnered the "Best Feature Documentary" Award for the 2013 Dallas International Film Festival, a Palm Beach International Film Festival Selection, and invites to film festivals that range from South Africa to Warsaw, Poland. They also won an award for Best Documentary at the Montreal International Black Film Festival.

"It hurts me that Olivia is not here anymore," says Jones. "But she's going to speak a little a louder from the grave."

Find out more about the film at :smallsmallthing.com

Find out more about the film at :smallsmallthing.com