By Peter Costantini, Seattle

Ten years after the contentious Seattle Ministerial of the World Trade Organization - AKA "The Battle of Seattle" - the relationship between trade, jobs, poverty and migration remains tangled and controversial.

Trade agreements make it easier for goods and services to cross borders. And beyond trade, strictly defined, many such agreements also include provisions making it easier for capital and transnational corporations to move around the world at will. These provisions sometimes try to facilitate international investment by redefining as trade barriers the regulations adopted by national governments on labor conditions, the environment, public health and safety, and human rights.

Trade agreements, however, usually don't make it easier for workers to relocate to other countries. But the effects of liberalized trade and investment on local economies often do give them reason to pack their bags and go.

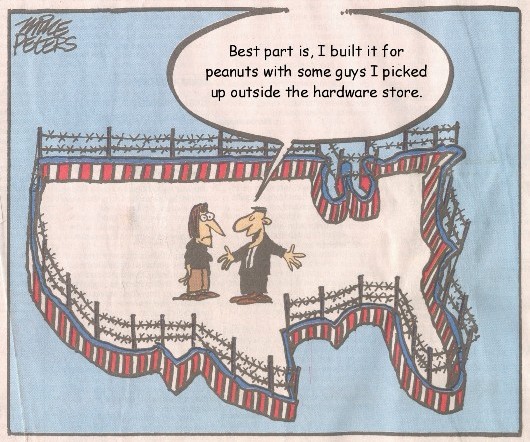

Drawing: Mike Peters, Dayton Daily News. Caption: Peter Costantini.

Drawing: Mike Peters, Dayton Daily News. Caption: Peter Costantini.

World commerce has grown rapidly in step with economic and social globalization. But as trade expands, the costs are often borne by people at the bottom of the economic ladder, as even the Director-General of the World Trade Organization recognized, according to a story by Isolda Agazzi of Inter Press Service.

"Trade liberalisation has transition costs and not all segments of society reap the benefits of it," said the WTO's Pascal Lamy. "Trade liberalisation creates winners and losers. Jobs are created but some are also lost, even if not permanently. Time is needed for adjustment. The extent of benefits from trade depends in part on how this adjustment occurs."

Lamy was reacting to the October release of a joint WTO / International Labour Organization report, Globalization and Informal Jobs in Developing Countries. The study found empirical evidence that loss of formal jobs and growth of the informal sector often appear to correlate with increased trade liberalization in poor countries. In much of the developing world, it pointed out, "a majority of workers are employed in the informal economy with low incomes, limited job security and no social protection."

"In some instances trade reforms have increased labour market vulnerabilities in the short term," the report concluded. Lamy, while saying he believed the problem did not invalidate the case for trade opening, acknowledged: "The reality of adjustment costs does caution against an easy assumption that simply opening trade is sufficient to secure development and greater prosperity."

Another report released earlier this year by the WTO and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that there is not "a simple and general conclusion ... on the causal link between trade and poverty, be it directly between the two or through the impact of trade on growth and, in turn, on poverty". Evidence of poverty reduction through trade liberalization is weak, the study found, and even where it does reduce poverty, it tends to benefit elites more and thus to increase income inequality.

When international trade polarizes societies and makes poor people poorer, it often uproots them and encourages them to move somewhere else to try to find a way to make a living. If they have to cross borders in search of their livelihood, trade can become a driver of increased migration. This frequently occurs where developing countries border on wealthy countries, as is the case between the United States and Mexico, as well as between Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

One of the now-classic examples of trade and investment driving migration is the fate of Mexican small farmers in the wake of the North American Free Trade Agreement. The Mexican government and businesses began to embrace economic liberalization several years before NAFTA took effect in 1994. But these trends accelerated rapidly afterwards.

The U.S. has continued to provide enormous subsidies to agriculture, most of them going to major agribusinesses. Corn producers in particular receive a big part of the support, driving down corn prices on the international market.

While the Mexican government provides small amounts of subsidies, nearly all go to the biggest agricultural interests there as well. Small farmers in poorer parts of Mexico, already suffering from roll-backs of land reform, loss of credit and weak market infrastructure, were washed off their lands by the opening of Mexico to tsunamis of subsidized U.S. commodities. Small corn farmers were among the hardest hit.

The number of unemployed Mexican agricultural workers rose to 6.8 million in 2004, according to the Economic Policy Institute, and rural poverty rates rose above 80 percent. Since NAFTA, over a million corn farmers have been driven off their land, many forced to sell at depressed prices, and wages for workers in corn production have fallen 70 percent, according to a report by the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

Under NAFTA, U.S. manufacturing lost significant numbers of jobs in sectors such as automotive, apparel, and electronics. In Mexico, some manufacturing sectors have become more profitable and created jobs. But many industries that depended on low wages have since left Mexico for Asia. Between 2001 and 2007, Mexico lost over 850,000 manufacturing jobs and real wages fell some 20 percent. According to a study of globalization and Mexican labor markets presented to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the wide gap between Mexican and U.S. wages has not closed significantly before or since NAFTA went into effect.

Where were all the economically displaced Mexicans supposed to go? For many decades, migration paths had been well worn by seasonal farmworkers between poorer areas of Mexico through the industrial farms and orchards of northern Mexico and up the U.S. Pacific Coast or through the Southwest. The influx swelled and diversified through the '90s and into the early '00s, although it has declined since the financial crash and economic meltdown. It flooded into cities and urban industries, and flowed out into new areas of the country such as the Southeast.

Trade liberalization does indeed create losers along with the winners, as M. Lamy candidly observed. Mexico and the U.S. may be a dramatic example, but it is only one of many. When there are enough losers, haphazard economic integration can be a powerful driver of migration. When globalized flows of goods, services and investment invade the communities of people already on the edge and uproot their world, border walls will not stop them from going wherever they have to go to rebuild their lives.

Last week Inter Press Service published my retrospective on the WTO 10 years after Seattle:TRADE: A Lost Decade for the WTO?

I covered the Seattle Ministerial in 1999 for IPS:The Tear Gas Ministerial

In 2001, I wrote and produced a web site about the WTO:What's Wrong With the WTO?

Lori Wallach, Director of Global Trade Watch, analyzed the WTO in The Nation:Obama's Choice

Kevin P. Gallagher and Timothy A. Wise, of Boston University and Tufts University, reviewed the NAFTA experience on the CIP Americas Program web site:Reforming North American Trade Policy: Lessons from NAFTA