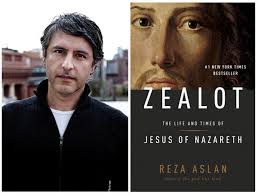

Writer and Scholar Reza Aslan's new book, Zealot, attempts to peel back 2,000 of Christian theology to reveal a very human Jesus living in radical political times. The author's source material is familiar to scholars; however, for this reviewer, at times it was interpreted too broadly. Aslan's most significant contribution is how, when possible, he transforms these ancient historical contexts into seamless narrative by using a three-act Structure. In Act 1 (pp 3-70), he depicts the centuries that led up to the expected Messiah and spells out what a promised king would have meant to a Jewish people under foreign rule. During Act 2 (pp 73-159), he introduces Jesus of Nazareth, the man, who, like his contemporary "zealots," fights for the rights of the poor and the overthrow of the state (Rome). Finally, in Act 3 (pp 164-216), Aslan spells out how the zealot Jesus, through the imagination of gospel authors, became the Christ.

Aslan does not tread lightly over the sensitive nuances of this terrain, as he begins his tale at the point of the sword, pointed by Jesus: "Do not think I have come to bring peace on earth. I have not come to bring peace, but the sword" (Matthew 10:34). Ouch, right there in Holy Writ. Jesus was not just a peacemaker who said "turn the other cheek" or "blessed are the poor," but also a sword-carrying rebel with a real agenda, or... a zealot. In other words, Jesus (the man) was willing to employ violence, as he did at the Temple, according to Aslan, which was why he was killed. And, according to Aslan, when it comes to Jesus as wisdom teacher or man of forgiveness, most of that was made up. I must confess, separating the human Jesus from the Christ figure of scripture is like parsing wheat from chaff during a windstorm.

Beginning with Jesus the man, who emerged in the wake of messiahs dead at the hands of Rome, Aslan does position his argument in a socio-political context, cross-referenced with secular sources and not too many leaps of faith. He also frames Jesus' character with an earthly motive shaped by Jewish expectations for the role of Messiah as one who will usher in his kingdom -⎯ so far so good. The conflict between Jesus and the Roman Empire, and his need for 12 apostles (representing Israel's tribes) to carry out the apocalyptic drama, is presented here as the central conflict. The story ends in 66-70 AD as the Romans crush Jerusalem, and early Christian writers are then free to extract the zealot from his homeland and recast him as a cosmic God-man.

Many scholars have fallen on their swords (pens?) in attempting this feat of plotting the development of early Christianity, which requires a journey from the Judean homeland to the far-off edges of the Roman Empire. The question is, did Reza Aslan reach his destiny?

Frankly, I don't think a book of 296 pages could successfully traverse this narrative nor its ancient terrain. As a literary critic, I might suggest that Aslan's Act 1 and Act 3 are strong, because they can rely more on what is historical. Act 2, the longest and most important, might need some work, because the period requires the mingling of theology and history and cannot be portrayed with secular conviction. In Act 2, at times Aslan would have been better served to acknowledge limited sources rather than continue with epic conviction.

Rather than review all of my minor points of disagreement, I prefer to focus on the book's overall three-act progression in order to reveal the main hole in Aslan's story. It occurs during the middle of Act 2 as we transition from this zealot, Jesus, to an emerging world savior, the Christ. The writer notes this pivot in the Gospel of Mark, written around 70 AD. Here, when it became clear that this Messiah who was a hostile Jewish Revolutionary would no longer appeal to a Roman audience, the early church writers begin a face-lift on Jesus. The problem is that the character and meaning of Jesus, in part, had been predestined at a much earlier point, dating back to the earliest sayings found in the gospels and written by none other than that supreme auteur, the Apostle Paul.

Paul was probably converted three years after the death of Jesus (36 AD?), when he experienced a vision (he never spoke of lights and horses). After 12 years of Paul's ministry, we have his letter to the Thessalonians, written approximately 48 AD, or 15 years after the death of Christ. All of Paul's letters (7-14?) that quote the earlier sayings and traditions (i.e., I Corinthians 15:3-8) were written before 70 AD; most scholars would argue that here Paul largely fashions the meaning of Jesus later integrated by the gospels. As a matter of fact, if we include Luke, whom Aslan rightly quips is "Paul's biographer," and his Luke-Acts two-volume history, 15 out of the 27 New Testament books were written by Paul or his followers. Citing Paul in one chapter (14), titled "Am I Not An Apostle?" in a Book on Jesus is like citing Mozart as an afterthought in the history of classical music. Paul and his conflict with the Jews in Jerusalem over the Gentile mission are the bridge that crosses the gap between the Jewish cult and the Roman religion. And yes, as Aslan argues, more mysticism enters the faith through Paul, in part due to the Greco-Roman audience. Yet the author forgets that it had always been Paul's practice with his own Jewish mysticism, well-documented by Jewish scholars. It's not so "either or" as Aslan puts it, either political or mystical; sometimes, in the case of Jesus, it is both: theo-politik.

Also, in Paul's theo-politik, God's divine plan is the true nexus between Jesus and Paul and their successive roles in the "coming Kingdom." Paul, a self-proclaimed zealot, believed Jesus had disclosed to him alone a vision of the "first fruits" of the Kingdom, which was a radical departure from the Jewish idea of general resurrection. He reasons that Jesus did not crush the Roman Empire because God, out of his mercy, allowed a time of grace for the Gentiles to enter the fold, the house of Zion. In other words, Gentiles needed to be offered entry, and Paul was the prophet called to fulfill the plan. Righteous judgment, or the final battle, as Paul refers to it, was with the "principalities of this world," the dark spirit behind Rome, only delayed.

Lastly, reading into history a neo-Marxian perpetual revolution against Roman power misses the central conflict at the core of the Christian faith, which was one of culture (ethnicity): the question of who was in and who was out. In light of the Messiah, who were chosen and who were not for the kingdom? Should the Mosaic laws apply? Jesus himself, when he cleansed the Temple of Roman influence, was defining these boundaries. No Roman (Gentile) money in my father's house! The Jewish War was the final blow to the Mother Church in Jerusalem, but it was long in coming. Moving west, away from Jesus' original teachings about the Torah, was the doing of Paul and clearly a position different from that of James and the Jerusalem Apostles, and a matter of no concern to the Romans, outside of collecting taxes or keeping the peace.

Whether the clash that propelled the Christian faith into the Western World was cultural and/or political, the truth is, like Paul or Mark or the human character of Jesus, we are all many things at once, which is why the modern use of the word zealot reads a bit strongly. Though it was neutral in ancient times, it now implies a disproportionate passion when seen in light of the humanity of others. Written with a fine narrative and colorful language, Reza Aslan's Zealot helps fill in the background world of Jesus from Nazareth. It reminds us that even our highest aspirations -- even divine meaning⎯passes through flesh, a fact that still goes largely unrecognized.