Acrobatics, music and animation feature in Monkey, Journey to the West. Photo: William Struhs.

Acrobatics, music and animation feature in Monkey, Journey to the West. Photo: William Struhs.

A flesh-eating skeleton, a seductive spider and a dragon king. These are among the mythical creatures Monkey encounters on a journey that has captivated for centuries.

The tale of Monkey and his companions -- greedy Pigsy, skull-wearing Sandy and the monk Tripitaka -- has proved an adaptable fable. Monkey, Journey to the West is a classic of Chinese literature and has spawned many incarnations. It's been turned into manga, cartoons and a cult TV series - one former Blur frontman Damon Albarn grew up with. Albarn has turned it into an opera which opens at the Lincoln Center in July.

In the opera -- designed by Albarn's Gorillaz collaborator Jamie Hewlett and directed by Chen Shi-Zheng -- Monkey eats heavenly peaches, is imprisoned by the Buddha and is chosen to accompany the pilgrim Tripitaka.

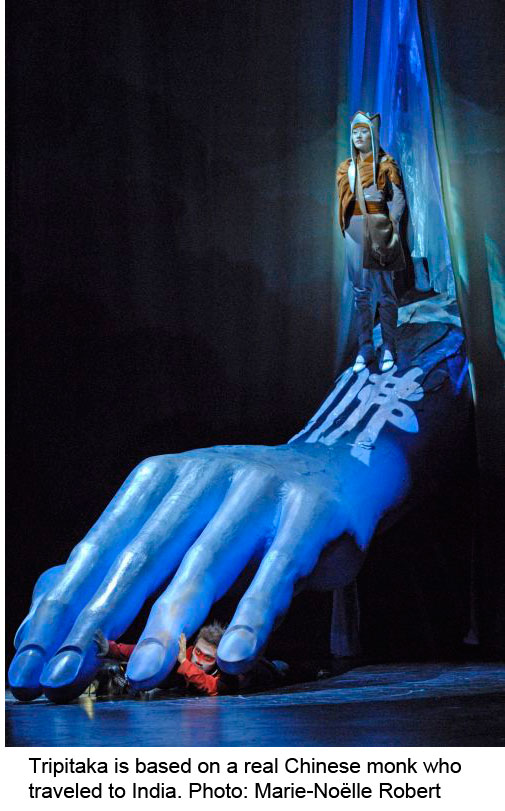

But the tale of Monkey has its origins in a real figure whose impact is still felt today. The saintly Tripitaka is based on a Chinese monk named Xuanzang who set out in 629 AD on what would become one of the great journeys of all time.

Like Monkey's Tripitaka, the historic monk's goal was India from where he wanted to bring back Buddhist scrolls. Unhappy with the translations of sacred texts then available in China, he went to Buddhism's birthplace in search of originals.

But it wasn't only what he returned with that has excited the world ever since. It was his observations during his epic 16-year journey that took him along the Silk Road, across the Gobi Desert, over the mountains of present-day Afghanistan and into Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka.

Xuanzang would prove himself an intrepid traveler, a brilliant translator and a remarkable eyewitness: part Christopher Columbus, part St Jerome and part diarist Samuel Pepys.

Xuanzang gave what is believed to be the first account of the then newly built Bamiyan Buddhas, the two giant figures that were blown up by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2001.

He described them as glinting in the sun with their gold paint and jeweled ornaments -- they must have been an astonishing sight. When Xuanzang arrived in Afghanistan, Bamiyan was a great Buddhist center.

He also described a third even larger Bamiyan Buddha -- a reclining figure. And it is because Xuanzang's written account has proved so accurate in its descriptions of places and geography, that in the past decade one Afghan archaeologist has been searching for this long-lost third Bamiyan Buddha, although so far the figure has not been found.

When Xuanzang's writings were translated into European languages in the 19th century, a generation of Indiana Jones-type explorers sought out the places he described and the treasures they might contain. These adventurers consulted the monk's writings like a contemporary traveler might a Lonely Planet guide. And they did not return empty-handed.

It is largely as a result of his writings that the place of Buddha's enlightenment at Bodhgaya was rediscovered together with the neighboring Mahabodhi Temple and the once great monastic university at Nalanda, whose ruins remain in northern India.

Monkey's greedy companion Pigsy is fond of women, food and more food. Photo: William Struhs.

Monkey's greedy companion Pigsy is fond of women, food and more food. Photo: William Struhs.

Today, these are pilgrimage centers for Buddhists worldwide. But little over a century ago, they had been all but forgotten, until British archaeologist Alexander Cunningham used Xuanzang's writings to locate them.

In Pakistan, the remains of one of the wonders of the ancient world, a giant monument known as Kanishka's stupa, was found near Peshawar just over a century ago, also with the aid of Xuanzang's writings. The monk estimated the height of the jeweled stupa, named after an ancient Buddhist king, at about 600 feet (183 meters).

Xuanzang's journey was every bit as eventful as Tripitaka's. He was attacked by bandits, captured by pirates, and almost offered as a human sacrifice to the bloodthirsty Hindu goddess Durga.

But he accomplished his mission. He returned to China with the scrolls he sought and spent the rest of his life translating sacred texts. His translations are still chanted in monasteries today.

Monkey, Journey to the West is at the Lincoln Center, New York City, from July 6-28, 2013.