"It is generally for two reasons that people feel urged to follow an artistic career: one is for the sake of honor; the other is for the sake of profit." Karel van Mander, Lives, 1603-04

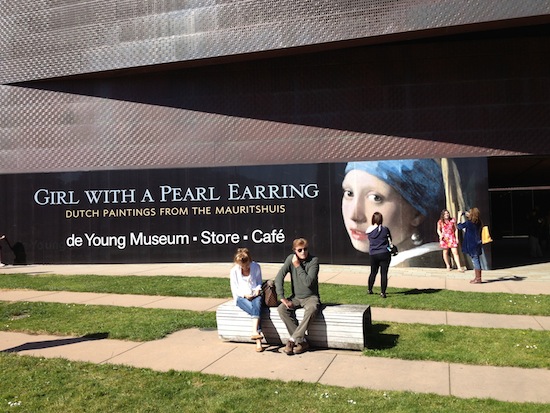

This Spring I visited The Girl With a Pearl Earring show at the de Young Museum in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park. It was a gorgeous sunny day, nevertheless I found myself spending many hours inside, astounded by the paintings from the Mauritshuis in the Hague, which is undergoing a major renovation. That excellent selection of 30 works is marvelously complemented by Rembrandt's Century, a collection of over 200 rarely displayed works from the collections of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Photo by the Author

Many of these are self portraits, or compilations (of portraits and biographies) of artists of the period. It was in fact one of the most popular genres - there was a "keen" and "brisk" market for these paintings. The artists wanted people to know who they were - notoriety was considered a good thing by some artists. The public loved to know as much as they could about their favorite artists, as evidenced by the many books written for the art-loving public.

While I was looking at a large painting by Van Steen - one of my favorites - a Dutch couple stood next to me and, noticing me smiling, studying the painting, the man said, "We call these Jan Steen households - or messy houses".

Jan Steen, As the Old Sing, So Twitter the Young, ca. 1668-1670

Oil on canvas, 523⁄4 x 641⁄8 in. (134 x 163 cm)

Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague

Acquired in 1913 with the support of the Rembrandt Society (inv. no. 742)

Image courtesy of the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis, The Hague

"The More of a Painter, the Wilder he is." 17th Century Dutch Proverb

That Jan Steen remark stuck with me, and a good deal of illuminating research has followed. Especially interesting are the more nefarious subjects, such as the new habit of smoking, the old habit of drinking, and of course carousing in taverns. "Dissolute' was the term used at that time, coming as it did from a powerful, newly-middle class society widely divided over it's religious beliefs and behavior tolerances. Painters of this sub-genre included Jan Steen (who came from a family of brewers and tavern operators), Godfried Schalcken, Frans van Mieris (who became Steen's drinking buddy later in life), Franz Hals, (who spent "more time in the alehouses then his studio"), and Adrieen Brouwer and his student, Joos van Craesbeeck above all.

Jan Steen, The Idlers, 1660

Oil on canvas, 30 X 39cm

Courtesy of The Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia

Godfried Schalcken, Lady, Come to the Garden, ca. 1668-70

63.5 X 49.5 cm

The Royal Collection © 2011 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II/The Bridgeman Art Library

Franz van Mieris, A Meal of Oysters, 1661

Oil on Panel, 27 X 20 cm

Courtesy of Mauritshuis, The Hague

Frans Hals, The Merry Drinker, 1628-30

Oil on Canvas, 81 X 66.5 cm

Courtesy Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Amsterdam

Adriaen Brouwer, Smoking Men, ca. 1637

Oil on panel, 46 X 36.5 cm

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Joos van Crasebeeck, Death is Quick, Quarrel in a Pub, ca. 1630-54

Oil on panel

Courtesy Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

They seem to be enjoying themselves. From Steen's painting of a smiling smoker behind a drunk maid who's lost her shoe, we come to Godfried Schalcken, who appears to have lost most of his clothes in a carefree game with several women. In van Mieris' painting, the woman receiving the oysters looks quite happy to be there. Franz Hals perhaps imitates real life with an offer of a merry drink. Adriaen Brouwer's smoking men confront the viewer with various methods of vulgarity, enjoying it as they do.

These images come despite a strong opposition to them. In 1628, a contemporary of Rembrandt's, the artist known as "Torrentius", Johannes (Jan) Symonsz van der Beeck, was tried and sentenced, and eventually put to death for his religious beliefs and for living a "frightful and pernicious lifestyle". From the time these paintings first appeared, they would have shocked some, and authors have posited varying reasons for these works, from them being cautionary tales to affecting irony and humor. The artists knew the possible consequences and benefits, and made the images anyway - they stand out for the fact that they are unique and bold.

Rembrandt, very famous for a time, and Judith Leyster, who was considered well known and even referred to as a 'leading star" of her day (partly based on her last name), painted pictures of themselves, even if only a few of the ill-repute variety. One of the most important aspects of this type of painting is that it often featured the artist in the title role - sort of extended self portraits. In the case of Judith Leyster, only two years after Torrentius's trial she depicted herself as a prostitute without causing any damage to her reputation as a painter within the society - perhaps she could have expected the opposite. In "Carousing Couple", 1630, Leyster paints herself as a rosy-cheeked, courtesan, happily leaning forward, offering wine - in other words, love - to her suitor, who pretends not to notice while he plays the violin.

Judith Leyster, Carousing Couple, 1630

Oil on Canvas, 68 X 54 cm

Courtesy, The Louvre Museum

In addition for the need to have some sort of reputation to go along with their skill in painting - good or bad - in order to command a market for their work, artists also had to deal with it's vagaries and difficulties, such as it's ups and downs due to war and economic issues, and popularity or fashion.

"Art is about bread." 17th Century Dutch Proverb

In the case of the Dutch Golden Age - from the early 1600's to around 1672, (when the French invaded) otherwise known as "the disaster", the entire art market - from the least expensive paintings to the most fashionable - was strong enough to create some of the greatest painters to pick up a brush, and generate somewhere between 5 and 10 million art works by the end of the century. The supply meant that prices were generally low for most paintings, which led to speculation on the much more expensive paintings. Naturally many people of the time, artists and critics especially, felt that only 10% or so were of any quality. Collectors bought them from the artists studios - which they were encouraged to visit - and from art dealers. There were also annual fairs and lotteries organized every year to sell the works. Art dealers were often criticized during their time for charging exorbitant prices for lesser works to un-educated collectors, who were often considered "blind" or "stupid", and often referred to as "naem-kooper" or "name buyers", who bought based on the fame and recognition of the artist, rather than the work itself.

In speaking about art dealers, one contemporary put it this way...

"...in many towns these Asses have so much credit that their judgement is valued above that of the honest connoisseurs."

Rembrandt had something to say on this subject, as we can see from his drawing, "Satire on Art Criticism", 1644.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Satire of an Art Critic, 1644

Pen & Brown Ink corrected with White on Paper, 15.5 X 20.1cm

Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It depicts an art critic pointing the end of his pipe at an artwork, offering his knowledge of the work, pretending to know his subject, with an audience in rapt attention - while paying no attention to the painting. The critic is an ass - drawn complete with asses ears. And staring us in the face is Rembrandt himself, pants down, happily finishing a shit. One writer has identified the critic as Andries de Graeff, who declined to pay the 500 guilders he owed for a portrait he didn't like in 1642. Rembrandt, alas, was falling out of favor with the public as he was painting "Satire".

A telling piece of advice given to artists of the time came from another contemporary, Hoogstraten:

"You have to arm yourself with tolerant patience in case of art lovers who have more money and power than knowledge, as it does not always fit to punish them accordingly."

Unfortunately, usually the painters from that era that we consider the best - Vermeer, Rembrandt, and many others as we've seen above, had to support themselves in other ways, such as running an ale house or dealing paintings. Many simply stopped painting when the market collapsed in 1672. They often ended up poor, penniless, sometimes with a large family to feed. That's one reason given in book about the recent attribution of several Vermeer paintings to his daughter Maria. His wife had to sell them as originals to pay major debts he left when he died - in a frenzy, his wife said - due to financial hardship.

"I have a genuine belief that art is a more powerful currency than money - that's the romantic feeling that an artist has. But you start to have this sneaking feeling that money is more powerful." Damien Hirst, artist; The $12 Million Stuffed Shark by Don Thompson, 2008

It's impossible, if you compare the Golden Age of Dutch painting with the present art world, not to see history repeating itself. The perceived value of the contemporary, high end art market reflects the exhorbitent prices being paid for it. Trouble is, historical value will not be known until most of the people buying and selling contemporary blue chip art are dead for a good long time. The over-speculation in the top end of the art market is obvious. Art works that sold for $5M a decade ago now sell for 10 times that.

It seems like every November and May, after the contemporary art auctions at Sotheby's and Christie's, there are articles about the Art Market Bubble. If you Google "Art Market Bubble" you'll find article after article, from the last crash around 1991 (due partly to the Gulf War) to the present, talking about when the bubble will burst, and even a trailer for a movie, from 2007 promising that it will burst immediately. Still, not even a pop..

A very recent letter to the editors of the New York Times, by William Cole, was headlined "Invitation to a Dialogue: An Art Market Bubble?" Mr. Cole asked, in part, when the emperor would be seen to be wearing nothing at all.

Adam Lindemann, in an article in the GalleristNY in 2012, observed that the idea of an art market bubble makes good copy, and that art and the art market are two different things, and pretty much dismissed the idea of a bubble.

Hyperallergic, in an article in January, says the art market in the grand scheme of things holds it's own, on a yearly basis, against some pretty major businesses, like tobacco and alcohol and Ikea.

Mark Speigel of Stanphyl Capital Management, LLC, who believes there's a bubble, and who says he did the math, posits that there's $1T (that's 1 trillion dollars) of art buying power in the hands of the very few people that can spend $25M on a work of art, which translates to 40,000 possible purchases of those art works. And, as he posits, there are only about 20 per year of those sold in an average year.

He's saying the available capital exceeds the supply of pedigreed art. (Why is "greed" part of that word?) In Mr. Speigel's opinion, those works have yet to be created - the bubble ain't gonna burst unless the "perceived value" of art is changed.

No matter your view on the subject of an art bubble, or lack thereof, it really only matters if you are in the business to speculate. The average artist who must keep working, even those making commercial work that's about as deep as the thickness of their canvas, needn't worry too much. The prices for these works remain relatively constant - under the range of, say $5,000 in today's prices - they almost always have. Even in the 17th century, paintings on the lower end of the totem pole sold for around 2 Guilders - $2,000 in present day numbers, consistently throughout the century.

Thankfully, since around 1450, when oil painting (as well as printing) techniques were refined, there have always been artists willing to take risks - in the best cases, compelled - to create work on spec, in other words, to create for it's own sake. (And of course, even those before and since who have a commission to paint or create have found ways to do their own thing within those systems.) And, for most, it wouldn't be a bad thing for others to know about it so they could make some more.

But to be honest about the art world, in the extremely narrow chance an artist has a solid gallery and collectors to keep their prices moving up, most artists' work will never command a higher price than the moment it's sold, much less sell for what was paid for it.

"...art is cheap but priceless, and blessed assurance very dear." Dave Hickey, writer/former gallery owner/dealer, "Dealing", Air Guitar, 1997

On October 27, 2012, Dave Hickey said he was quitting the art world because it's "nasty, stupid", and in part because in order to sit on a panel discussion at the Guggenheim in NYC, he was required to sign a 10 page contract. He refused.

So, in other words, do your art or your dealing or your collecting or your writing about art because you love doing it and can't think of doing anything else, despite market changes, war, pestilence, disease, or panic. And - while you're at it - enjoy a little bit of history.

Both shows closed Sunday, June 2. The Girl With the Pearl Earring will travel to Atlanta's High Museum of Art before moving to The Frick Collection in New York in October.

The author is indebted to Ingrid A. Cartwright for her excellent thesis project on the subject of dissolute portraiture in 17th Century Dutch painting.

For further information on the contemporary art market, visit Art/World.