For several days, the winds from the destroyed nuclear reactors at Fukushima Daiichi crashed head on into the myth of the radioactive plume.

It is the most enduring falsehood of commercial nuclear power, promoted heavily by both the industry and its watchdog, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. It is a myth with two conflicting premises:

• Radioactive gasses spewing from a stricken reactor or spent fuel pool have an inherent property which holds them in a tight, thin stream which prevents widespread contamination.

• At 10 miles the plume disperses like steam from a teapot, leaving traces that are either too small to measure or are so minute as to be "below regulatory concern."

The contradiction between being tightly bound and widely dispersed is never challenged. It was most clearly enunciated at a public hearing April 8, 2002, in White Plains, New York, on the evacuation plans for the two Indian Point reactors, located about 30 miles north of Manhattan, owned by Entergy Corp. There was no dissent from NRC officials as Entergy's Larry Gottlieb said, glibly, "the easiest way to avoid a radioactive plume is to cross the street.

"It's kind of like someone pointing a gun at you and all you have to do is step to the left or right to get out of the pathway of the bullet. That's all you have to do."

During the frenetic first week after the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami destroyed the infrastructure of Japan's northeast coast, killed some 20,000 people, and set four of the six Fukushima Daiichi reactors on an irrevocable path to meltdowns, officials from the U.S. Departments of Defense, State, and Energy, as well as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission clung to the notion that the situation was manageable as long as the "plume" held true to the myth and blew out to sea.

That was paramount to DoD, which had 63 military installations throughout the Japanese islands containing some 60,000 men and women and their families. It was a relief, therefore, when the aircraft carrier, the USS Ronald Reagan reported March 13 that its sensors were picking up radioactive material on its flight deck, 130 miles off the coast.

According to the NRC Status Report, "The measureable radioactivity was consistent with the venting of the Fukushima Daiichi Unit 1 reactor. The Navy also collected air samples having activity above background from the 'plume'. Analysis, the report states, would show the Reagan contaminated with "iodine, cesium and technetium, consistent with a release from a nuclear reactor."

And that was good, because the plant operator, TEPCO, maintained that the reactors were under control and radiation stemmed from planned venting of built-up gasses, not from a complete meltdown. As long as the radiation was staying in a plume blowing out to sea, there would be no need to evacuate all the American bases, or the millions of residents in the Tokyo metropolitan area.

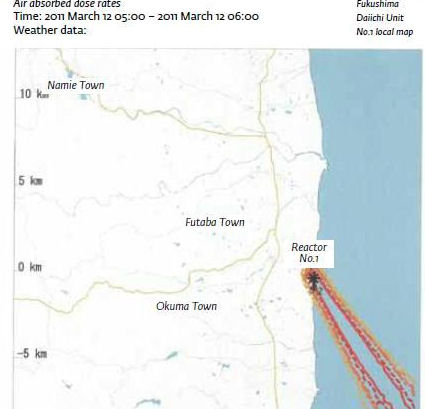

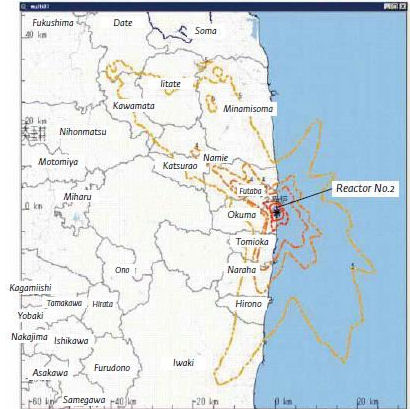

In reality, Fukushma Unit 1 began to meltdown as a result of the earthquake, before the tsunami hit and destroyed all backup power. The molten core of the reactor would melt through the reactor vessel and containment, crashing into the water below the reactor and sending radioactive steam surging out of the damaged building. Monitoring stations, which were not analyzed till January, 2013, found radiation rose more than 700 times the background levels at least an hour before the venting. Officials assumed the Reagan detected a controlled plume which, in fact, had not yet been created. Instead, the ships were in a radioactive cloud which had not been anticipated.

What TEPCO did not say -- and what American officials overlooked in that hectic period -- was the fact that the venting did not work.

"The difference between Chernobyl and Fukushima," said nuclear safety engineer Arnie Gundersen, "was that the fire at Chernobyl sent the radiation high into the atmosphere and it was widely dispersed. There was no fire at Fukushima. You had those beautiful venting towers, but the vents were inoperable because there was no power to activate the industrial fans.

"So the radioactive steam just rolled out and over the countryside like ground smog. About 80 percent of it blew out to sea."

And the discrete plume was a myth. The Reagan and its attendant warships constantly attempted to dodge a mythical plume when, in reality, there was a spreading cloud continually overhead and increasing amounts of contaminated currents all around them.

By March 16, after explosions had destroyed the buildings housing Fukushima Units 1-4, Kurt Campbell, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian Affairs, officials at the NRC and DoD were increasingly upset with the Japanese government for relying on TEPCO for information rather than taking charge.

Asahi Shimbun, the Japanese newspaper, reported that "an internal report on the issue secretly circulated among top State Department officials on that day contained one word -- 'FUBAR' --or Fu**ed Up Beyond All Recognition."

Continue reading at Energy Matters.

A Lasting Legacy of the Fukushima Rescue Mission Part 1: Radioactive Contamination of American Sailors

Part 2: The Navy Life -- Into the Abyss

Part 4: Living with the Aftermath (forthcoming)