Thousands of red, orange and green prayer flags dance around me, leaping and falling and twirling as the wind pushes the air, thin at 18,700 feet, over the shrine. I can barely believe my legs have carried me this far so I savor the last of my last energy bar in an effort to stay in my body's good graces. Lyrical prayers I can't understand resonate across the mountain walls.

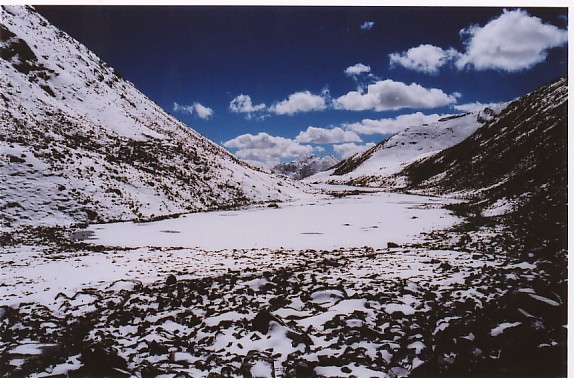

Struggling to stay conscious, I gaze at the rocky, snow covered ground, taking deep breathes of shallow air.

I stood on the Dolma-La Pass, the highest point of the four-day kora, or hike, around Mount Kailash in Ngari, or Western Tibet. Our 12-person group took days to drive our Landcruisers across the Tibetan Plateau to even get to the base of the mountain; the Tibetan and Indian pilgrims -- who prostrated their whole bodies over and over on the ground -- took two years to get there. For the Hindus, this "diamond in the sky" is the abode of the Lord Shiva. For Tibetan Buddhists, it's the home of the Buddha Demchok, who represents and grants supreme bliss. For me, it was a place where I could barely walk and had no idea what was happening around me.

I had been infantilized by a mountain.

Tibet itself seemed like a sacrosanct crystal on the roof of the world, a novelty more than an actual place I could roam across for months. It was a place of deep green, flowery fields and icy overpasses where we often backpacked 23 mile in a day. I found myself alongside yaks, other travelers (but rarely Americans), nomads and wild dogs believed by Buddhists to be monks who had misbehaved in a previous life.

Lhasa, the capital, is where our journey throughout various parts of the province started and ended, where we rested there before heading into the mountains that enshrined us. On calmer days we ascended only the stairs of our run-down hostel. In Tibet, the average altitude is 16,000 feet so this was no meager feat.

Off The Beaten Track

The twelve of us on the trip, first confronted the country in a traditional Tibetan square in a midst of a city with a rapidly growing Chinese population. In the heart of Lhasa, strip malls replaced shrines, Chinese signs were four times as big and numerous as Tibetan ones, and paved roads with taxis left rickshaws battling the forces of traffic.

Inside the Bharkor, where Tibetan rather than Chinese words drifted in the air, we'd wake up at 5 a.m. by the rooster outside. We would follow each other in silence over the few remaining rustic and broken cobblestone roads, taking in the smell of fresh momos (potato or yak meat dumplings), gazing at the tall, ironically named freedom poles and the vendors selling prayer flags, cheap jewelry and singing bowls. All the Tibetans that passed greeted us with a friendly "Tashi Delek." There were monks holding hands in friendship, old men playing pool to the side of the road, laughing children running around each other in circles, short women with worn faces and long, sharp, black hair woven with colorful ribbons, and lots of goats wandering the road for food scraps.

Chinese security guards stood in front of the Jokhang Monastery and the Potala Palace, the former home of the Dalai Lama, armed with rifles and collecting 100 yuan -- currently about $17 -- from tourists just to enter. We did not. Security laced the stone walls to make sure no one misbehaved by saying "his" name, or possessing a picture of him. We always had to refer to him, the Dalai Lama, as "The Boss." There had been many recent cases of Chinese military guards dressing up as Tibetan monks, asking hapless tourists for pictures of His Holiness, and then arresting them. In 1959, after a national uprising against the 1950 Cultural Revolution and take-over by Chinese communists, the Dalai Lama fled from the Potala Palace to Dharamshala in northern India for safety, where he went on to form the Tibet Government-in-Exile.

For the next 20 years after the uprising, 1.2 million Tibetans, one-fifth of the country's population, perished in prisons and labor camps. Militants destroyed over 6,000 monasteries, temples, and other cultural artifacts. Before the Chinese take-over, a "Degree for Protection of Animals and the Environment" had been renewed every year by Dalai Lamas since 1642. But since 1950, half of Tibet's forests have been cut down, and nuclear and hydroelectric projects have abounded.

The current Dalai Lama has both discouraged and encouraged tourism to Tibet: On one hand, he says, tourists support the oppressive Chinese government every time they buy a permit to enter. On the other, he once announced, outsiders should visit not only so that they can see how bad the situation really is, but also understand why it is important to keep the culture and the beautiful landscapes of Tibet alive. Maybe if they understand, he's proclaimed in numerous speeches, they will be inspired to speak out.

Traveling throughout the countryside and on our final trip to Kailash, it was hard not to be impressed and feel lucky to see what remained before another 54 years passed. We spent our first night at the Ganden Monestary (12,467 feet) adorned with elaborate Thongka Paintings and brass Buddhas, and filled with monks who offered us tea, laughter, and old Indian action movies in Hindi. A two-mile hike into the rolling hills and through a valley lead us to a Sky Burial Site, where old bones juxtaposed a rainbow forming in the dewy, grey sky. In Tibetan Buddhism, death is simply a moment of sacred transition, a time of giving back to the earth. In what most Westerners would consider a morbid act, the dead are taken by monks to these sites, graced heavily by vultures, and chopped up and left to decay into the cycle of life.

At the nearby Drepung, the largest monastery -- or gompa -- in Tibet, we witnessed monks debate religious teachings in the courtyard, pounding their fists on their palms to stress their points taken from their eight hour sessions of study during the day. Before 1959, the monastery was the home of 15,000 monks; today that number is down to 3,000.

Afterwards, we ascended by foot into hillsides and vast open fields graced by wild yaks, which looked like restless storm clouds when I'd view them from my tent at night.

Meeting The Locals

Getting closer to Kailas, we camped out on the plains near the Terdrom Nunnery, or anigompa in Tibetan. Here the anis, or nuns, lived in small villages next to a river at 16,000 feet. After our usual dinner of rice noodles, cucumber, eggs, and yak-meat for the non-vegetarians on board, a small nun with rosy cheeks approached me.

"Kherahng kusu debo yinpo?" I asked her, meaning, "How are you?"

She pressed the back of her hand to her forehead, feigned collapsing on the ground and then looked up, smiling. She spoke in English. "I'm tired," she said.

We laughed, and she invited me into her small hut at the bottom of the hill for tea. I followed her, taking big steps which she tried to mock with her little legs. In the hut, which consisted of one room with a stove and bed in opposite corners, I sat on a large wooden chair, listening to the stream outside rush by in the dampness of the early evening. She gave me a cup of yak butter tea, and laughed as I inadvertently cringed when I took the first sip.

For the next two hours, we conversed the sparse phrases of Tibetan I'd picked up, her broken English, and through photographs. In a huge album, she showed me snapshots friends had taken of Lhasa, "the big city," and how she's always wanted to see the Potala. Next to a photo of the ten story palace tucked behind plastic coating, she showed me the 22,000 foot (6,700 m) Kailash looking regal behind clouds. Before leaving, I gave her my only spare photo of me, which she had me sign before placing it into the large book.

"Simja nango," or "Good night," we both bid each other before I returned up the steep, cold hill, falling into a deep sleep, the first sleep where I didn't have lucid dreams of my bed at home. In the morning, after a breakfast of thugpa, or noodles, we walked eighteen miles, before Landcruisers took us an extra five hundred towards Kailash.

Recommended Reading on Mt. Kailash and Tibet

Circling the Sacred Mountain: A Spiritual Adventure Through the Himalayas: A first hand account of a Kailash kora from renown Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman.

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying: A spiritual masterpiece about Tibetan Buddhism with applicable insights on making the most out of life.

Resources

"Obtaining a Tibet Travel Permit": Good advice on securing the Chinese Visa and paperwork needed to enter Tibet, especially for independent travelers.

The Land of Snows: Expert and honest advice on journeying through all parts of the country.