Dance in the round is rich with possibility. Each viewpoint offers a chance to present a different aspect of the moving body, with no one angle being definitively "right" or "best." As someone who's performed Merce Cunningham's landmark in-the-round work Ocean, choreographer Jonah Bokaer knows that firsthand.

The brand-new Fisher building at the Brooklyn Academy of Music features a blackbox whose chairs can be arranged in myriad configurations, and for ECLIPSE, which inaugurated the theater last week, Bokaer and collaborator Anthony McCall choose to put seats on all four sides. McCall, known for his cinematic light installations, adds yet another dimension to the stage with his striking visual design: a cascading plane of bulbs suspended from the ceiling, which glow in subtly shifting patterns. They light the way as you enter the theater and choose your seat, a small constellation of reachable (and for the less graceful, bump-into-able) stars.

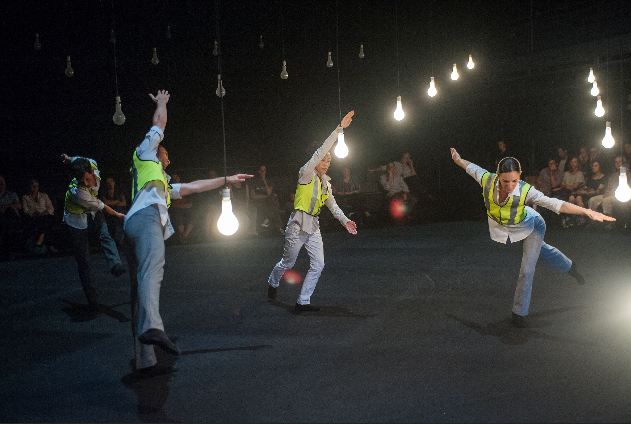

The audience isn't just all around ECLIPSE; ECLIPSE is all around you. David Grubbs' sound design broadcasts the low whirr of a film projector from each of the theater's four sides in turn. The dancers -- Tal Adler-Ariele, CC Chang, Sarah Procopio, Adam Weinert and Bokaer -- enter and exit from all four corners, melting in and out of view.

Adam Weinert, Tal Adler-Arieli, CC Chang and Sarah Procopio in ECLIPSE. Photo by Stephanie Berger.

Bokaer's choreography is soft and lush, edgeless, hypnotic; his dancers never seem fully awake. At one point Weinert and Adler-Ariele perform a duet involving a string of unlikely connections -- shoulder on shin, foot on back, chin on foot -- but, even when strained to their limits, they maintain an otherworldly coolness. In ECLIPSE Bokaer also seems preoccupied with symmetry and roundness, with four dancers retreating repeatedly to the four corners of the room, or gathering in a circle around the centermost bulb. Structurally the piece runs a circle, too: It begins with Bokaer willing bulb after bulb into illumination with a hand, a knee, the back of his neck, and ends with him extinguishing bulbs, one by one, the same way.

Each of ECLIPSE's four sections is marked with a blackout, punctuated by the deep rumbling sound of a passing subway train or the roar of a jet engine, before the projector whirring begins again from another side of the theater, announcing that the dance has resumed. There's something soothing about that marking of time, which quickly becomes predictable and familiar. In a different work, it could feel a little cute. Here, as the light-stars wink on and off, it gives the sense of cosmic forces in balance, of a cycle of days, years, eons. When Bokaer kneels to extinguish the final, lowermost bulb, we hear the sound of the tape reaching its end and beginning to flap around the still-spinning reel. Bokaer rises and spins in time with it, a celestial object in revolution, as the light fades to black.

--------

A former dancer and choreographer, Margaret Fuhrer is an associate editor at "Dance Spirit" and "Pointe" magazines.