The surgeon cut open my chest. He held my heart in his hands. I had suffered a major heart attack. I came to the hospital expecting to have a stent placed in my heart. By the time it was over, I had undergone quadruple bypass open heart surgery. Doctors put me in a medically-induced coma for four days. At one point the chief surgeon told my brother that it might be a good idea to says his goodbyes. My heart -- damaged much more severely than even surgeons had anticipated -- was in danger of rupturing. As the real-life drama played out in intensive care, my Facebook "friends" took to the "newsfeed" and my "timeline." They flooded the pages with an outpouring of prayers and affirmations of faith and hope. The social network site that marks milestones and celebrates birthdays has become our modern-day town crier. It can announce to hundreds of "friends" and "friends of friends" not only a life-threatening illness but the moment of one's death as well.

As I lay intubated and still, a machine breathing for me, friends provided Facebook with frequent updates. My brother Bill said my face looked ashen. A former cop, he told me that he had only seen that gray color on the faces of those close to dying. He had flown into New York City from Weston, Fla. to be at my side. And as I hovered in between life and death, the many prayers and even Catholic masses being held for my recovery became an "electronic novena" of sorts. And it played out with my Facebook friends not only locally and across the country, but around the world as well.

How did I get here? It all started a few days earlier as I rode in a car with friends to Fire Island. I was suddenly hit by what I thought was a severe case of heartburn. But the pressure in my chest was much more than indigestion. My friends suggested I pop Tums.

I remembered that a few years earlier I had felt the same kind of pain. Weeks later my doctor concluded, during a routine physical exam and EKG (electrocardiogram test) that I had suffered an apparent "heart episode." It was called a "silent" heart attack because the symptoms mimic other maladies. Heart attack victims don't always grab their chest dramatically and fall to the floor and die like they do in Hollywood movies. Often they live through the attack and, left untreated, the damage to the heart only intensifies.

The next day I felt feverish and listless. I took the ferry back from Fire Island. I was rushing back home because I was scheduled to participate in the annual AIDS WALK NY. I had raised $1,500 for the Keep A Child Alive Foudation and GMHC (Gay Men's Health Crisis). I didn't want to disappoint the many friends who had supported me by pledging their hard-earned cash.

Feeling fatigued, I took asprin and downed over-the-counter flu remedies. By the next morning I felt a little better. I walked 6.2 miles. The next night I attended a play, but I could barely take in a breath -- I took a cab to St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital Emergency Room. Tests concluded I had indeed suffered a "heart incident." Three days later I was visted at my bedside by cardiac surgeon Dr. Daniel Swistel. He explained that tests concluded I had suffered damage to the heart that required surgery the very next morning. He discussed the possibility of placing a "stent" in my heart. According to the National Institutes of Health, a coronary stent is a small self-expanding metal mesh tube. It is placed inside a coronary artery to prevent it from closing. The procedure does not involve open heart surgery.

The next day I finally emerged from the six-hour surgery. I remember being wheeled on a bed down a long and winding hallway. I thought I could hear a mysterious sound like someone gently passing their fingers over a xylophone. It turned out to be the sounds from the machines that were keeping me alive. It seemed that I could make out twinkling lights above me. I felt at that moment that I had not survived the surgery -- that I was witnessing my death. "I didn't make it,' I remember thinking. Doctors say that people placed in medically-induced comas can still hear. And a few seconds later through half-shut eyes I thought I saw a familiar face. My brother Bill whispered into my ear: "Charlie, it's going to be all right. Joy (my sister-in-law) and Summer (my niece) send you their love. I am here now. It's all right. You can come back to us," he said. With those words I felt a glimmer of hope. If my brother was here whispering in my ear, perhaps I was alive after all. I fell into a deep, long sleep.

My brother walked over to the nurse's station to get more information accompanied by two of my closet friends, Daniel Greenstone and Matthew Carnino. Dr. Swistel, still in surgical scrubs and cap, overheard their conversation. The surgeon began to speak. "I'm Dr. Swistel. I operated on your brother. I had his heart in my hands," he said. "Did you know that your brother had a heart attack in 2003? It was a major heart attack that caused a lot of irreversible damage. Apparently they treated it medically and just sent him on home. When he had his most recent heart atack, the heart sustained even more damage. He took Tums for something he should have known was a heart attack. Instead of seeking medical attention. He walked 6.2 miles in a walkathon. He waited until the next day before coming to the hospital. We did a quadruple bypass on your brother's heart," he said. "Then, I discovered the walls of your brother's heart between the areas that had been damaged to be paper thin. Your brother's heart could explode. I had to put a patch over the area of the heart that was paper-thin to bolster that area. (The rupture) could be a few minutes from now. It could be a few hours. So you should go in there and say your goodbyes to your brother."

My brother and my friends say they stood like statues as they heard the words. Then he offered a ray of hope. Dr. Swistel said every 24 hours without an incident meant the heart was trying to heal. I could still make it.

My brother thanked Dr. Swistel. My close pals, Matthew Carnino and Daniel Greenstone, told me they wept. They took to Facebook to share the critical turn of events. The next morning Matthew and Daniel's first post on my timeline appeared: "(We) are posting to inform you that Chuck's situation is heartbreaking and the next 48 hours are critical. Please take a moment now to say a prayer and send positive energy." The reaction was overwhelming. Hundreds of people -- some I didn't even know -- began offering prayers and healing energy. Friends in turn "shared" the postings. "Prayers, prayers, prayers, prayers," wrote Virginia Hogan Spitzer. "Prayers from the West coast," wrote Tommy Hickey from Arizona. From Caracas, Venezuela to Rome, Italy, Facebook friends sent in their messages of hope. "Bombard Chuck's sprits with prayers and positive thoughts," wrote, Sheila. One posting by Matthew two days after the surgery elicited 46 seperate responses -- positive affirmations of hope. Shelley Ross urged friends to increase the money donated in my walkathon above the $1,500 mark. Some friends asked their parishes to say Catholic masses in my name. Michelle Gillen, a long-time friend and journalist from Miami wrote: "Just spoke with him before the (AIDS)walk. I called to tell him how proud I was and impressed with his amazing [blogs] for The Huffington Post. At the end of the day he is a journalist and those words he shared are his legacy."

As I lay in that coma -- "bombarded" by so many positive thoughts and prayers -- it was almost like I could feel the power of the sentiments. They seemed to give me strength. And indeed, if one believes God or a Higher Power can answer our prayers then Facebook's timeline had become my lifeline. Four days after I was placed in a medically-induced coma, I began to blink. "Come back to us," my brother had whispered right after the surgery. And I did.

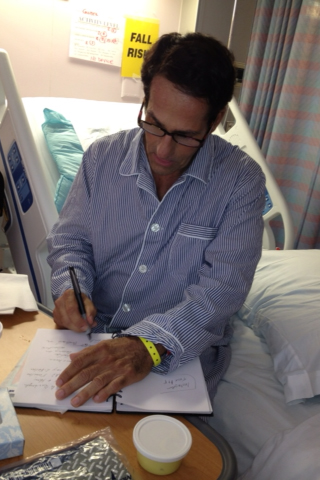

After two weeks I was learning to walk without a cane. I was sitting up and eating in bed. A skilled team of physical and occupational therapists at St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital helped me with my agility and endurance. Slowly, I got better. The ashen-faced patient doctors had once given 24 hours to live was finally on the mend. Longtime friends came to visit. My spirits were lifted. And one friend in partcular, journalist Michelle Gillen, flew in from Miami and sat next to me on my hospital bed. She looked me in the eye and smiled. "You must begin to write about your experience," she said. She pushed a journal into my lap. I began to write.

I remembered the words Facebook friend Glenys Vargas from Rome, Italy posted on my timeline as I lay in a coma. "Chuck, you will make it. I see it. I feel it. I know it. I will wake up to see your new post in The Huffington Post on how you made it through."

Yes Glenys, I made it through. And here is the post you wanted to see.

For more by Chuck Gomez, click here.

For more on heart attacks, click here.