When Avatar was released in 2009, it was consistently and annoyingly referred to as a game-changer; even critics who derided the film's lack of narrative depth couldn't deny its impressive use of cutting edge technology to create an entirely new world rather than simply enhance some version of our own. I have to imagine films like Avatar are why the Academy Awards developed categories zeroing in on technical achievements, even as soon as the earliest shows in the 1920s and 30s, so that a problematic but still astounding film like Avatar can win Best Cinematography even while losing out to the grittier pleasures of The Hurt Locker when it comes to Best Picture.

This past year not just one but two different documentaries from New German Cinema auteurs have employed 3D technology to create new and exciting ways of seeing the existing world, an endeavor surely as admirable as Avatar's pursuit of cinematic fantasy, yet they have hardly received anything close to an equal level of fanfare from the Academy. Werner Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a survey of the historic cave paintings of Lascaux, some of the earliest human artworks ever discovered, and Wim Wenders's Pina, a visually stunning look at the work of late choreographer Pina Bausch, both received high critical praise and the latter an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary, but the final list of nominations gives neither of their technical achievements any notice; those awards may as well not exist for documentaries.

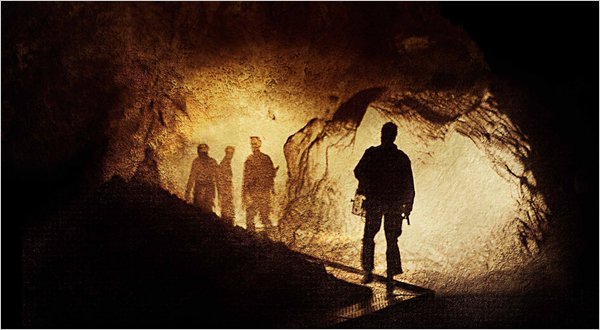

3D nonfiction has long been a staple of IMAX theaters in amusement-type venues like zoos and aquariums, which use the technology to take us on a journey to the bottom of the sea or the furthest reaches of the Milky Way. Cave of Forgotten Dreams, with its desire show a rarely seen natural wonder, shares some DNA with such IMAX fare, at times resembling more straightforward scientific films a little too closely. It's a bit on the straight and narrow for the usually much stranger, heavier hand of Herzog (the coda, a contemplation of albino alligators in voice over, being the glaring exception), despite touching on the paintings' larger implications about the nature of art and human existence. If only the film contained more of Herzog's traditionally irksome, pretentious, but ultimately evocative musings on life, death, and the cruelty of nature, it might have broken free of any mundane associations and earned an 2012 Oscar nomination for Best Documentary (or at least a spot on the documentary shortlist). Even so, I find it perplexing that Herzog's detailed exploration of the caves, a beautiful record of a notoriously delicate ecosystem shot in the most challenging of conditions, was not seriously considered for Best Cinematography. Herzog used the third dimension in exactly the way an audience intrinsically craves: to feel they are in the space depicted onscreen, and the fact that in this case that space is real but accessible only to a handful of the world's top scientists makes this experience an awe-inspiring, wholly unique adventure.

While the visual and technical achievements of Cave of Forgotten Dreams are somewhat marred by more conventional approach to content, Pina is at least as innovative in its storytelling as it is in its filmmaking, seamlessly integrating dances staged in unconventional public settings, culled from archival footage, and performed in spaces created for the film, with a flowing editing style that more closely resembles dance intuition than cinematic logic, and generally approaching the idea of capturing dance on film by blurring the lines between these two arts, in many instances through the use of 3D. While Pina was nominated for Best Documentary rather than being relegated to the even more obscure ghetto of Best Foreign Language Film, the Academy failed to recognize, where critics and audiences around the world did not, its pioneering spirit and challenge of what is given the 3D treatment and how it is done. Equal parts avant-garde jewel and accessible spectacle, Pina is lovely and thrilling, not only one of the best documentaries, but one of the best films of the year, and for qualities that make it deserving of nominations for categories like Best Cinematography and Best Editing, among others.

The sad reality is that, for most Academy voters, pitting documentaries against features would be comparing apples to paltry, second-class, never-gonna-beat-an-apple oranges. While I hardly want to advocate a longer show to accommodate a preposterous number of awards, and having to make a dupe of every category for docs feels a bit like a minefield of cinematic affirmative action, perhaps creating special doc categories, particularly in technical fields, is better than letting the work and talent of hundreds of artists go overlooked.

There is, of course, a longer conversation to be had about why documentaries can't stand up to narratives when it comes to award shows in the first place. While documentaries are technically eligible for awards in categories like Best Special Effects, Best Art Direction, Best Editing, or Best Sound Editing, they are simply never nominated, sometimes quite literally never. Just think: the Best Cinematography category has feted the less memorable work from Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home and Tootsie, but can't make room in its nerdy little heart for Robert Flaherty's groundbreaking Louisiana Story, or the epic chronicle Battle of Chile by Patricio Guzman (whose film Nostalgia for the Light was robbed of a nomination in multiple categories this year, incidentally), or the Maysles' wildly influential and unforgettably stylish Grey Gardens, or, more recently, the latest of Frederick Wiseman entries like La Danse and Boxing Gym? What grander achievement can there be in cinematography than taking something we know and have possibly even seen on film before -- like a historic cave or a simple piece of choreography -- and transforming it, using the tools of cinema, into something both more real, and within grasp, yet more transcendent, and magically ephemeral, than ever before?

An earlier version of this post mistakenly mentioned Nanook of the North as an Oscar contender for Best Cinemotagraphy.