By no grand design, the last two books I've read--Philip Roth's American Pastoral and Bruce Springsteen's Born to Run--while disparate in tone and content, both use the story of richly detailed, postwar New Jersey upbringings to tell the story of mid-century America. Both books by my heroes left me in awe and with a classic case of writer's schadenfreude. (For the record, that's different from Shonda-freude, which is writer's envy about not having a show on ABC's Thursday night lineup).

In my case, my envy wasn't just about their prodigious storytelling talents or anger that they were able to get past page three of writing a book (though that's obviously part of it. Have we met?). But for me, the real envy came from their richly detailed sense of place. Whether it's the kosher butcher shops or glove factories of Jewish Newark or the emotional bipolarity of the mixed Italian-Irish homes of Freehold or the girls in their summer clothes walking the boardwalk in mid 60's Asbury, these all felt like stories that needed to be told. From places that were interesting enough to have stories. That's what always makes me most jealous as a writer: people who have such a clear and specific sense of place.

Because when I start to think about my own stories, my own upbringing, the voice in my head speaks back to me in the same sad-sack cadence of Charlie Brown getting a rock. And it says to me "I'm from the Valley."

At first glance (and many glances after) being from the Valley feels like the equivalent of being from nowhere, of growing up no place. To borrow from the parlance of the pharmaceutical industry, the Valley in the public's mind has often stood as the generic for "bland suburb." Every time I try to write about my youth-- and hats off to P.T. Anderson, but I always have trouble trying to wax poetic about a place best known for backyard porno shoots, liquor stores, Valley Girl accents and Quizno's-laden strip malls.

Sure, in the Val of the 70's, kids rode dirt bikes and wore pooka shells. Girls had feathered hair. Guys had feathered hair. Chachi had glorious feathered hair. So did Kelly Leak. Kelly's hair and panache not withstanding, I always empathized more with Jose, Miguel and Rudi Stein. And obviously I longed to possess the sabermetric genius of Ogilvie. Somehow to this day, The Bad News Bears still plays as a more verite version of Valley living than any of my home movies.

As I've begun to write my personal things and have also fancied myself as a douchily self-appointed "Bard of the Boulevard", I've started to look closer at the specifics of growing up Jewish in Encino. The quirks, the mores, the Sunday night dinners where you recognize nearly everyone at Fromin's or Emilio's, the multi-corn dog binge fests in the stands of Encino Little League.

After a half dozen years in Van Nuys, I spent the formative part of my youth living in the Jewish Alps, the kosher canyon, the mean streets of Encino. The closest we came to violent crime was my family of origin robbing me of my self-esteem at brisket point. Quick, cross the street. Those Ashkenazi kids and their one Korean friend may try to sneak a peak at my AP Bio homework.

Looking back, Encino of my era was so Jewy that I never even realized it. I just assumed everyone was until starting Episcopal boys school, but that's another story. Seventies Encino was the kind of place where the census taker would measure each home's men, women, children and Purim carnival goldfish. There were so many Fila sweat suits, you'd think you were at a Bjorn Borg cosplay convention. Men of that era were certainly partial to mustaches and permed Jewfros. At least six men on our block appeared to graduate from the Alan Dershowitz School of Modeling. The women ranged in height all the way from 5'3 to 5'3. And apparently that didn't bother me. Even today, when shopping at Gelson's in Encino, surrounded by yentas in yoga pants, I often think to myself "this must be what normal guys feel like at the Playboy Mansion."

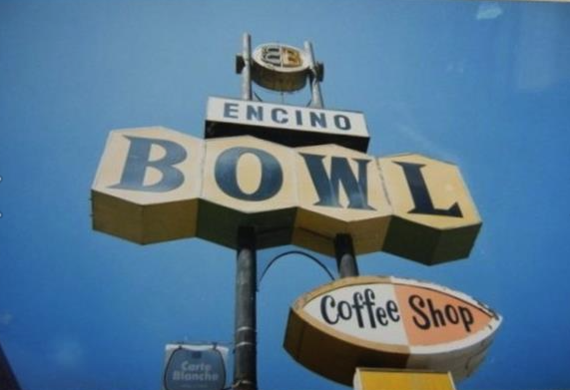

In many ways, it was the gauzy, halcyon suburban childhood of Super 8 movies and retro Polaroid filters. Even at 8, my brother would ride bikes, unsupervised, from Encino to Sherman Oaks. Spend all day trolling the boulevard, riding from the Wiener Factory to Sav-On Drugs to the La Reina theater to the newsstand on Van Nuys for the newest wrestling magazines. Or Mad. Or Cracked. We had a pool at our house. We had a pool at our beach club. Even our shul had a pool. I definitely remember a large part of growing up in a wet bathing suit. For those who were there, there was Encino Bowl, Boys Market, Pages, Mike's Pizza, Harry Harris shoes, Carney's, Terry York Chevrolet. We'd play pinball at Golf Land, ride go- karts at Pepe's, eat ice cream at Thrifty's or Baskin-Robbins or Swensen's. There was even a hot dog shack/ batting cage, Flooky's, right there on the boulevard.

Our biggest celebrity was the perfectly-coiffed, appropriately sleazy Larry from Three's Company. I didn't know the real person. But nobody better represented the slightly second-ratish, slightly disco Valley guy on the make than the character of Larry Dallas. When it came to actual guys on the make, there was nothing like the bar scene at Stanley's. The men were attired in what can only be described as a proto-Tommy Bahama, Valley Vice look. I remember one night I saw that OJ, Marcus, the Boz and Pat Sajak were all on the prowl at the bar the same night. And rather than be disgusted, I was filled with an odd amount of valley pride and grapefruit chicken salad.

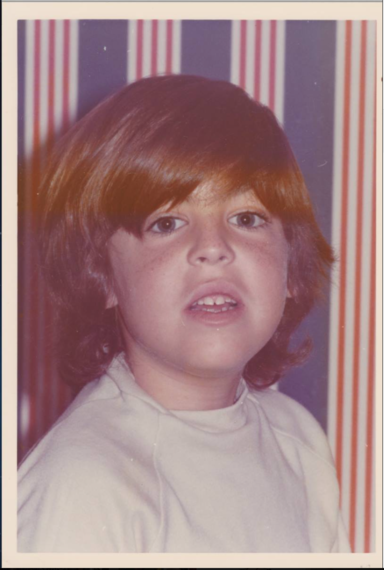

Mind you, it wasn't all perfect. Nowhere would be for a shy, sensitive little Hebe with severe panic disorder and a childhood propensity for drawing his own colored bar graphs. Let's face it, nobody becomes a comedy writer because they were "too popular" in elementary school. I transferred into Hesby, the public grade school halfway through kindergarten. And though my memories are mostly fond, I was bullied for bad breath, bad hair, being new, seeming old. I was the only kid in my in-class straw poll that supported McGovern over Nixon. (Yes, kids loved Nixon! Or loved going with a winner). I didn't kiss a girl until I was nearly the same age as Josie Grossy. And I showed up for the first day of first grade with a Julia lunchbox. Diahann Carroll in a nurse's uniform. In their defense, the children at my bus stop might've had their kid cards revoked if they hadn't beaten me with it.

Even today, the gauze of memory still competes with the more adult, bittersweet feelings that come from parental loss, of fractured family dynamics. As with anything, it's hard to see the past without looking through the prism of the present. It's funny, I vowed to never move back to the Valley, a stance that lasted as many minutes as it took me to read the Westside real estate section once. Now, I've figured that I've lived within walking distance of Ventura Boulevard for 30 of my 50 years. 35 if you count Sherman Way. That's even more 818, even though it was at a time that predates 818. We were all 213 back then.

Also, with age, I've come to terms with Encino, with the Valley as a whole, as not a generic place to be from. In two generations, it's gone from farm land to America's prototypical white flight suburb to an ethnic polyglot that in many ways mirrors the city many had tried to escape from.

I've also come to accept with Encino as a valid place with equally valid stories to tell. In fact, they described this sort of coming to terms better than I ever could in the first episode of The Wonder Years, which is still my favorite pilot ever. Sorry Sully. At the very end, after kissing Winnie Cooper for the first time, adult Kevin Arnold narrates "I think about the events of that day again and again and somehow I know that Winnie does too, whenever some blowhard starts talking about the anonymity of the suburbs or the mindlessness of the tv generation. Because we know that inside each one of those identical boxes, with it's dodge parked out front and it's white bread on the table and it's tv set glowing blue in the falling dusk, there were people with stories. There were families bound together in the pain and the struggle of love. There were moments that made us cry with laughter. And there were moments, like that one, of sorrow and wonder." And that's basically what Encino was like. Just with more lox and hair product and tennis jackets and Torah portions and pooka shells.