Last week I watched Ava DuVernay's powerful documentary on the history of racial inequality in the United States, titled 13th after the Constitutional Amendment that, in a seeming paradox, abolished slavery and entrenched racial hierarchy at the same time. How?

The film pulls viewers through a popular history of former President Richard Nixon's infamous Southern Strategy, and its relation to the history of crime policy in America. Much of this had been previously detailed by Michelle Alexander, (who is featured in the film) in her book The New Jim Crow. Importantly Alexander described how even as the blatant racism of the KKK fell out of favor with mainstream politicians over time (the current campaign of Donald Trump notwithstanding) politicians developed coded language that allowed them to play off the racialized fears of voters without using obviously racist language.

In the film, DuVernay cites former Nixon aide John Ehrlichman, who told Harper's:

The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I'm saying? We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.

DuVernay also plays tape of Ronald Reagan operative Lee Atwater explaining the next phase of dog-whistling.

Omitted from the film, but solidly positioned within this historical trajectory of the committed synergy between law enforcement and political motivation forged through the operationalization of mythologies of black criminality, is Broken Windows Policing.

Broken Windows Policing, of course, was introduced to a specific demographic of the public in a famous 1982 article by George Kelling and James Wilson in The Atlantic. However the theory really came of age, in a practical sense, a decade later when Bill Bratton, at the helm of Rudy Giuliani's New York Police Department, made it a household name. This was the latter-half of the "tough on crime" era during which Democrats like Bill Clinton veered from traditional party talking points to try to match "tough on crime" Republicans step for punitive step, as DuVernay details in the film.

During the early 1990s, violent crime had peaked in New York City, but New Yorkers were also aggravated by obvious signals of poverty: the squeegee-men, homeless people asking for loose change and sleeping in the parks. At the same time the Mollen Commission was publishing damning reports that reflected the public's declining confidence in the police.

"New York City Police Department [has] failed at every level to uproot corruption and had instead tolerated a culture that fostered misconduct and concealed lawlessness by police officers," wrote Selwyn Raab in the lede of a New York Times story on a Mollen report in 1993.

While solving murders was difficult, especially with corrupt cops, the police could make quick work out of the impoverished people out front in the public's eye -- burnishing the credibility of both politicians and the NYPD at the same time.

Bratton, nothing if not politically astute, engaged in a dual-pronged strategy to link people who were perceived to be disorderly as potential perpetrators of violent crime and to change the laws to give police more opportunities for interactions with the public, and arrests. What followed was a radical mass-arrest experiment that targeted almost exclusively people of color and others otherwise marginalized by a variety of public policies.

"For the cops [this was] a bonanza," Bratton said, as cited by Bernard Harcourt, one of the first academics to explicitly push back against Broken Windows policing. "Every arrest was like opening a box of Cracker Jack. What kind of toy am I going to get? Got a gun? Got a knife? Got a warrant? Do we have a murderer here? Each cop wanted to be the one who came up with the big collar. It was exhilarating for the cops and demoralizing for the crooks."

Of course we later learned that this "bonanza" was mostly false. Less than 1 percent of the nearly 700,000 people stopped in 2011 through stop and frisk (that we know of) were carrying a weapon, and less than 10 percent were doing anything that the police could eventually charge as criminal (barely any of these resulted in criminal convictions). "A lot of criminals are bad drivers," George Kelling said in 2013 advocating for the utility of more traffic stops as a deterrent to violent crime -- of course out of the nearly 1 million traffic stops in NYC each year, only a small handful lead to criminal allegations of any kind.

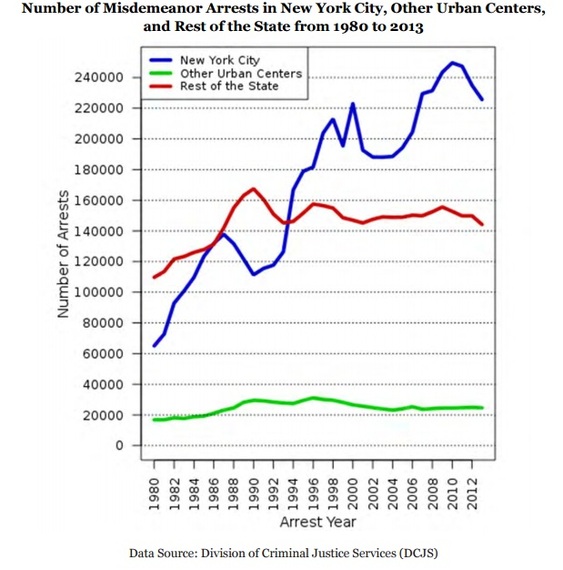

Since Bratton first unveiled this new policy, more than 8 million New Yorkers -- the entire population of the city -- have been arrested by the NYPD, the large majority of them for petty, low-level crimes, and violations -- behaviors that do not even rise to the level of a crime. The vast majority people of color.

And yet, due to the cultural work linking general disorder to violent crime, which had been previously racialized through Southern Strategy politics, there was little resistance from anyone in a position of power or authority. A decade later Kelling would crow: "This is not just smart policing; it's smart politics."

As described in DuVernay's film, we cannot understand American society without considering race at the center. It's impossible to imagine any policing practice in the U.S. today that will not have a disparate impact on people of color, because the police are operating in a society in which racial hierarchy is fundamental. Broken Windows, by opening up the greatest possible number of people to police interactions necessarily resulted in tremendous racial disparities.

Using coded language about disorder, and linking those deemed to be disorderly as likely to commit violent crime -- a dubious link to begin with and one that has been debunked in study after study since -- Bratton and Giuliani were able to push through regressive policies that would not have been possible absent the subconscious triggers about violent crime and mythologies of black criminality.

(We saw Bratton do the same more recently with gang indictments in New York -- fully demonizing large groups through the media, prior to mass arrests that otherwise might have been questioned by civil libertarians and perhaps liberal politicians if the subject groups had not been thoroughly "criminalized." This is classic moral panic work.)

Following in the Democratic trend started by Clinton, Broken Windows policing has been supported by a wide swath of liberal politicians, as an anecdote for abusive policing and even mass incarceration; yet, at the same time the policy reinforces many of the structural systems that makes abusive policing and racial profiling so prevalent. The social repercussions of arrests, even for the most minor of crimes can be devastating and long-lasting; when entire communities are targeted, the burden expands.

DuVernay, in 13th, and Michelle Alexander in The New Jim Crow, show how racism, operating through the criminal legal system, adapts over time to cultural norms while consistently producing the same outcomes. Chattel slavery, convict leasing, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, broken windows, predictive policing and the surveillance state.

So is Broken Windows Policing just another link on the ideological chain connecting Ehrlichman and Atwater, through Clinton and locally to Giuliani, Mike Bloomberg and finally to the New York City we have today: one whose claim as a progressive capital is not obviously frustrated by mass-scale arrests of people of color. More than 600,000 people were summonsed or arrested in New York City 2015; 85 percent people of color. A town in which we see outrage at police captains caught on tape telling officers to "arrest male Blacks," but not a peep from politicians about policies that have this very effect.