Hampton University junior Talia Sharpp knew she had to come correct when she told her mother about plans to switch from a business major to political science so she could study the Black Panther Party. You see, Terri Sharpp, her mother was clear about "no basketweaving" classes and choosing a major that would deliver a high return on investment.

"I'd have to be able to rationalize the decision I made to my mother," says Talia, 20, who is in a fellowship program preparing her for a full ride through her doctoral studies, a huge part of the appeal she made to her mom through text messages.

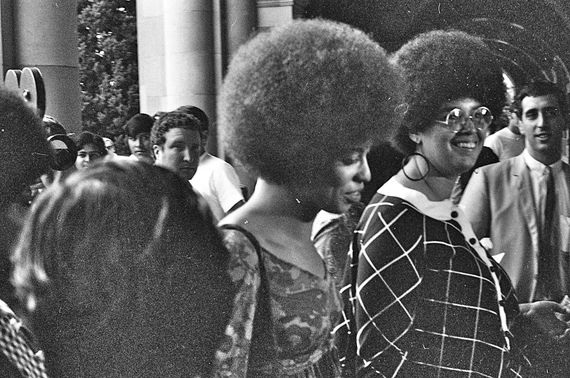

Angela Davis (center, no glasses) enters Royce Hall at UCLA in October 1969 to give her first lecture.

Such rationalizing is part of a national trend as college students balance their passions with the need to give parents a high ROI on the dollars they're spending -- and borrowing -- to make college a reality. Washington Post writer Steven Pearlstein captured this angst recently describing a trend among students being pushed toward science and math majors and decidedly away from the liberal arts: "I found it shocking that some of the brightest students in Virginia had been misled -- by parents, the media, politicians and, alas, each other -- into thinking that choosing English or history as a major would doom them to lives as impecunious schoolteachers."

If so many parents feel this way about liberal arts in general, what does that mean for Black parents when their college-age children announce they are majoring or double-majoring in Black Studies? At a time when Black Studies and its counterparts are providing the talking points for social policy and protest -- from state violence, and health care and education access, to activist professional athletes, is it fair to question the quest to explore the liberal arts from a Black perspective? Not everyone is happy with the notion of Black Studies, as a hostile Chronicle of Higher Education column shows.

"In terms of thinking about some of the most pressing issues we are facing together, like what it means to say Black lives matter or to talk about a police state or carceral state, Black Studies has been at the core of addressing those ideas," says Minkah Makalani, Ph.D., an African and African Diaspora Studies professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

"In terms of thinking about some of the most pressing issues we are facing together, like what it means to say black lives matter or to talk about a police state or carceral state, Black Studies has been at the core of addressing those ideas," says Minkah Makalani, Ph.D., an African and African Diaspora Studies professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

Currently working on UT's Black Matters international Black Studies conference on Sept. 29-30, featuring Lezley McSpadden, Saul Williams and Angela Davis, Makalani explains how scholarship and grassroots organization are symbiotic: "For example, Barack Obama has been directly informed by Black Studies and people who work in Black Studies. [The discipline] can have very real consequences for our electoral lives."

Makalani and colleague Daina Ramey Berry, Ph.D., make a point that the ability to think critically and analyze life-or-death issues is sorely missing in the current social and political climate. But beyond the basic skepticism and fact-checking required to listen to political discourse today, Black Studies provides a way for African diasporas to find common ground, which can lead to common solutions to long-term issues that affect Black people globally. So, for example, when the conference convenes a panel about Black women and anti-Black state violence, not only will American victims like Rekia Boyd, Sandra Bland and Natasha McKenna be addressed, the experience of Black Brazilian and Colombian women also will be uplifted and critically analyzed.

"Particularly in this moment when everything is about how much you can make in this or that field of study, at the same time there is a very real way Black Studies can raise important questions," says Makalani, suggesting ethical questions can influence scientific research or how to ask certain types of questions might be informed and improved by understanding a person's history or cultural context.

But beyond the basic skepticism and fact-checking required to listen to political discourse today, Black Studies provides a way for African diasporas to find common ground, which can lead to common solutions to long-term issues that affect Black people globally.

To be sure, Black Studies veers from typical liberal arts because it has an activism component, says Ramey, a noted genealogist who consulted on the "Roots" remake among other productions. The interplay between the classroom and the streets can be seen and heard by youth activists who are very comfortable with using words like "misogynoir" and "intersectionality," terms born of the Black and Africana studies movement.

"Being able to think critically can lead to actions with concrete goals or to written reforms with create roadmaps like the Black Panthers' 10-Point Program or the recent reparations 10-point program, which will be explored in special issues of Black Studies journals," according to Ramey Berry, noting this sort of scholarship is better poised to influence social policy and turn into laws that improve the Black condition than empty rhetoric that dominates much of the public conversation.

Speaking of the Black Panthers, that's exactly why Talia Sharpp, switched majors. She became enthralled with Huey Newton in a freshman year class but saw a large gap when it came to women of the movement, now her area of research. The party's philosophy didn't address patriarchy or uplift the thought of Black women, who still found other ways and movements to make their wishes known.

As for her mother, Terri, she's on board with Talia 100 percent:

"I'm old school," says Terri, who concentrated in accounting in college. "This is the fear a lot of parents have: Tuition is too high not to have a job when you get out. The biggest thing is she has a plan."

Deborah Douglas is a Chicago-based writer and lecturer at Northwestern University.