Richard Wagner was his favorite composer and Arno Breker his official house sculptor -- but Adolf Hitler's taste in art was surprisingly broad -- and gaudy -- judging by a vast archive of some 11,000 Nazi-era exhibition installation photos now published online for the first time.

The "Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung 1937-1944" database lists the Führer as the buyer of some 1313 artworks from the eight grandiose (and heavily-sanitized) exhibitions put on by the Nazi party before and during the Second World War at Munich's Haus der Kunst. Among the works on which Hitler spent some seven million Reichmarks were a bust of Mussolini's head, paintings of playful leopards, and Anna Elisabeth Rühl's sculpture of a donkey.

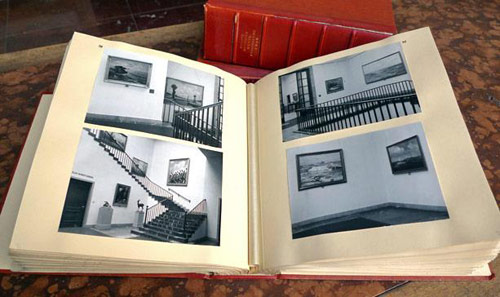

A photo album of the 1938 "Great German Art Exhibition" / © Central Institute for Art History, Munich

The project is the culmination of years-long research and digitalization by the Haus der Kunst and the Central Institute for Art History after researchers began unearthing the forgotten images from the Haus archives in 2004. Together, they suggest a Nazi curating style that was less totalitarian than fractional, beset by factional differences.

"We have to rethink some very easy and clear-cut prejudices," Dr. Christian Fuhrmeister, who spearheaded the project at the Central Institute, told ARTINFO.

In 1933, Hitler grandly promised that Germany would have the world's finest art, and the dictator put a definite end to the avant-gardism of the Weimar Republic. To make good on his claims, he became the country's biggest collector. But beyond proud eagles, muscular athletes, and the regime-glorifying works of Breker and Thorak -- and despite the ban on most modern works as "degenerate" -- there was no real consensus on the nature of true national socialist art.

There were works by Edmund Steppels, the quasi-Surrealist and former pupil of Max Ernst. In 1937, works by Rudolf Belling were presented both in the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung and in the derisive "Entartete Kunst" exhibition, showing confiscated works that were denounced as having insulted Germany and its people, or possessing what Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels termed a "perverse Jewish spirit." "Today, the challenge is to grasp these contradictions that no one thought about," said Dr. Fuhrmeister.

"The archives reveal that only a minor part of the works admitted to the exhibition openly depicted themes of National Socialist propaganda. A large amount of the works belonged to landscape and genre painting. Small-scale sculptures -- mostly of animals and female nudes -- had a much greater quantity than the monumental heroic sculptures," said Okwui Enwezor, today's director of the Haus der Kunst. "Hitler's collecting gives us an insight in how banal most of these art works were, and that the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung mainly reflected the taste of a dictator."

Still, the photographs are full of diversity. Seeking to represent all generations of Germans, the exhibition juries accepted soldier portraits painted by a 16-year-old Hitler youth as well as works by a 70-year-old professor. The exhibitions spanned every German region. And the selection process was riddled with infighting, said Dr. Fuhrmeister. "You have a rather heterogeneous and dynamic situation, starting in 1934 when they were discussing Expressionism," he said. "You saw continuous fighting between various institutions about national socialist art. This was a contested field."

The traditional view of totalitarian, top-down curating has endured, in part, because much of the writing about Nazi-era art has been based on the old exhibition catalogs or newspaper reports. Their black-and-white images were mainly of works referencing state iconography, propaganda and the military, which were considered most relevant at the time. It fit nicely with the assumption that Nazi Germany was a monolithic state where Hitler saw all and ruled all. "When you look at the art and art politics, you get a very different picture," said Dr. Fuhrmeister. "You now have this huge mass of rather petty-bourgeois, 19th-century-style painting, of landscapes, flowers, still life and so on." A few of these did also make it into catalogs -- but not in proportion to their vast numbers, he noted.

Since 2007, the researchers have been identifying the more than 12,500 works shown in the pictures, from old paper catalogs, curator's hand-scribbled notes with occasional mistakes -- and the Haus der Kunst's old accounting ledgers that only identified works by cross-referenced numbers. None of the photographs were precisely dated and some showed artworks that were not in the catalog, or omitted works that were.

"We had thousands of exhibition views, with no idea what we were looking at," said Dr. Fuhrmeister. "You have images from the opening, but after a few months, some works were sold and taken down -- and others brought up from the basement and put on the wall. Sometimes, particularly in the case of Hitler photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, works were rearranged specifically to create a more impressive array of images -- then put back in place." Little information was available for the years 1937 and 1944, so the researchers had to reconstruct those exhibitions visually. They perused the Bavarian state and Munich municipal archives for log books and went through the some 700 oil paintings today housed in Berlin's Deutsches Historisches Museum.

Visually, the exhibition views are a dull crop, and the German media has gleefully greeted their "immense boredom," as Die Welt described it. The debate about showing Nazi-era art has been controversial over the past decades, and some still subscribe to German-born Jewish art historian Nikolaus Pevsner's famous assertion that any word said about Nazi architecture is a word too much, extending this opinion to visual art.

"This kind of talk does not belong to art history at all," insisted Dr. Fuhrmeister, noting that copyright issues -- since few of the artists' works are yet in the public domain -- had been much more worrisome than debates over old taboos. "The Central Institute is housed in the Nazi party's former administration building and developed after America chose the site for its art institute and restitution work after the war -- so for us, the legacy of national socialism is a common, everyday experience. We would not accept any taboos or restrictions. We saw that the difference between what the literature says about national socialist art and what you see in the photographs was so big that we had to bring this new material into the scholarly discourse, and perhaps change its perceptions."

The Haus der Kunst itself is "a testimony of the time," said Enwezor. "I am of the opinion that we absolutely have to not only show the material in our archives, we have to properly contextualize it and defetishize it." He added that for its 75th anniversary next year, the Haus is planning an exhibition based on its archives, and that of the Große Kunstausstellung, which took over the mantle of great exhibitions after the Nazis and until the 1960s.

-Nicolai Hartvig, ARTINFO

More of Today's News from ARTINFO:

How Do Performance Artists Make Any Money? A Market Inquiry

Like what you see? Sign up for ARTINFO's daily newsletter to get the latest on the market, emerging artists, auctions, galleries, museums, and more.