British infantry advancing during the launch of the Somme Offensive, July 1, 1916

The Somme Offensive

By 1916, British casualties on the Western Front had amounted to more than 400,000 men dead, wounded or missing. 20,000 new volunteer recruits were needed every month to replace the casualties. Troops from Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa had arrived to join the struggle. More than one million Empire and Dominion men had been deployed, and many were now enroute to the Western Front. Another major offensive was about to be launched.

The assault that led to the Battle of the Somme had been planned as far back as late 1915. Originally it had been intended as a joint French-British operation. French General Joseph Joffre had wanted the battle to drain the German army of reserves while simultaneously making territorial gains, much as German General Erich von Falkenhayn had viewed the Battle of Verdun. In the end, it was Verdun that led to the Somme offensive being brought forward a month to July 1, 1916.

That date is inscribed in the annals of warfare as the bloodiest day in the history of human conflict. The first day of the offensive, launched on an 18-mile front north of the Somme River, between Arras and Albert, accounted for casualties of 58,000 British troops, a third of them killed.

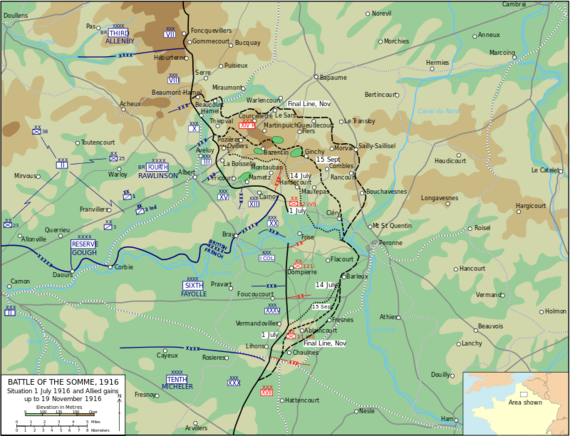

Map of the Somme battlefield

The assault had been preceded, as was the norm, by an artillery bombardment of the German lines that began on June 24, and continued for eight days. Three thousand guns - half British, half French - dealt the heavy blows that were supposed to obliterate the forward German defenses. In theory, this bombardment would enable British troops to saunter across no-man's land meeting little resistance.

The infantry attack was to be supported by a creeping barrage of artillery fire, aimed just ahead of the advancing troops and moving forward as the men advanced. Field Marshal Haig ordered General Sir Henry Rawlinson, whose Fourth Army would spearhead the assault, to consolidate after a limited advance, while to the north other forces would attempt a complete breakthrough of the German defenses.

Haig, a cavalry man, was convinced that horse-borne forces would be able to deliver the coup de grâce once the German lines had been breached, and open the way to the towns of Cambrai and Douai. The numerical odds were stacked in favor of the attacking British; they had 27 divisions consisting of 750,000 men, while the German defenders had 16 divisions of the 2nd Army on hand.

What Haig's planning failed to take into account was that the artillery's shells - more than 12,000 tons of explosives - would prove unequal to the task of destroying the enemy's front line barbed wire or robustly built concrete bunkers. Many shells failed to explode. The German troops, safely dug into the chalk hills, simply took shelter in their bunkers until the bombardment stopped and then emerged unscathed to man their machine guns.

The assault on July 1, was announced with the detonation of a 40,000-pound mine. It had been laid, after seven months of tunneling by Royal Engineers, beneath German front lines on Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. That massive explosion was followed ten minutes later, at 0730 hours, by the detonation of 16 further mines and the first wave of troops going over the top with bayonets fixed. Not surprisingly, given the amount of warning the Germans had been given by the bombardment and the failure of the artillery to break the defenses, those troops met with little success.

Canadian artillery battalion during the Battle of the Somme

They met, instead, deadly machine gun and rifle fire that killed them, wounded them or forced them back into their trenches. Many of the soldiers, weighed down by heavy supplies and expecting an easy passage to the German lines, took no more than a few steps before being struck down by the defenders. Further south French forces, whose offensive had been preceded by a much smaller bombardment, were more successful, but even they could do little more than consolidate their small gains rather than exploit them.

Nevertheless, despite appalling losses, Haig persisted with his approach, believing as the battle raged on, that the Germans would eventually succumb to exhaustion and that victory was imminent. Small advances were sometimes made, but they were short-lived and never followed up. German commanders took the opportunity to transfer troops from Verdun, doubling the number of defenders, and reorganizing their lines.

The British made use of tanks for the first time in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette on September 15. A total of 15 divisions supported by "tanks" were deployed, but gained less than a half-mile of ground. The original number of 50 lumbering "land-ships" - "tank" was purely a cover name that has stuck - had been reduced to 24 by mechanical and other failures. While the tanks had the desired shock effect on German troops, they proved unreliable and difficult to control. Some infantry troops even took friendly fire from the tanks.

British Mark 1 tank at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette

The battles continued throughout October, at Morval, Thiepval Ridge, Transloy, Ancre Heights and Chaulnes among other locations and, as French forces started to gain ground at Verdun, Joffre urged Haig to carry on. It was essential, he reasoned, that the British should continue to occupy the Germans while French forces continued to push back German forces at Verdun.

So it went on until, on November 13, Britain launched what would turn out to be its final effort of the Battle of the Somme: the Battle of Ancre. The battle resulted in the capture of the field fortress of Beaumont Hamel.

On November 18, hampered by snow, the Somme offensive ground to a halt. It had gained the British and French allies roughly seven miles of ground and cost around 420,000 British and 200,000 French casualties. On the German side, losses were estimated at half a million.

If there was one positive aspect of the Somme, it was the British re-evaluation of the usefulness of smaller tactical units of infantry troops. Beforehand, commanders had argued that a company of 120 men was the smallest effective unit possible; afterwards, they often followed the example of the French and Germans in opting for platoons of ten or so men.