It's not often that a reform Jew needs what's called a get -- a divorce decree that is usually reserved for the most observant Jews. But not long ago, Ellen, my ex-wife, asked me to give her a get. She isn't suddenly going deeper into Judaism; she's just dating a man who is conservative, which means that she will need a get before they can marry. (If they wish to. Eventually.) She had to ask me because tradition dictates that the ex-husband present the get to his ex-wife.

I had no problem with this. Ellen and I are very close, still, and I didn't want to stand in her way, whatever her plans may be... or whatever they become. We got the name of a rabbi in Lakewood, New Jersey, which has a very large orthodox population as well as Beth Medrash Govoha, the largest yeshiva in the United States (6,000 students). I texted him, and then we spoke and made an appointment.

What I pictured was that Ellen and I would walk in, sidle up to a window, answer some questions, say a few prayers, sign the forms, and then the get would be ours. I figured this was a sort of DMV for Jewish divorce.

Not so much.

What actually happened was rather more complex -- and a great deal more emotional.

Ellen and I entered a second-floor room in Lakewood's Congregation Ohr Meir. At least ten men were there -- a minyan -- the number of Jewish men needed to conduct a religious service. They were bearded and wore black suits and keepot. There was also a scribe, who looked a lot like Dumbledore, but Jewish. The rabbi we'd spoken with -- a younger man than I thought he would be -- ushered us in, sat us down, and started the proceedings. At this stage, it was mostly a Q&A session between the rabbi and me. Was I here of my own accord? Was I coerced in any way to be here? Had Ellen and I already had a civil divorce? What were our fathers' Hebrew and American names?

I was surprised no one asked about our mothers. After all, one is only Jewish if one's mother is Jewish.

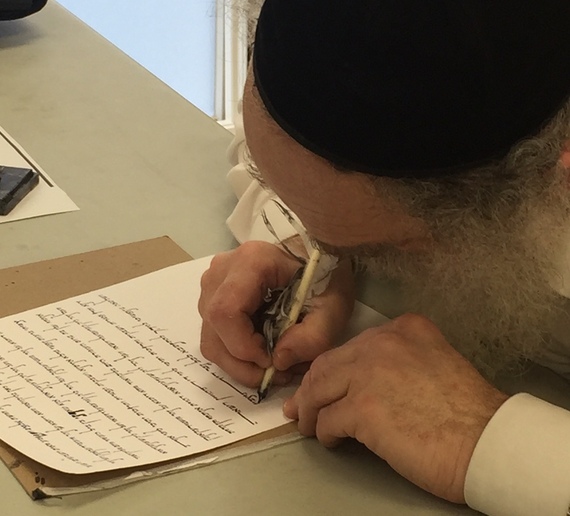

Once all the questions were answered and information gathered, the time came for the get to be written. It's supposed to be written by me, but my Aramaic isn't as up to snuff as I would like. Anyway, that's what the scribe is there for. There's a ritual, of course. With a warm smile, yet very officially, he presented me with the necessary tools in a black plastic box, and then I presented them back to him. Inside the box were a prepared piece of parchment and a quill fashioned from the feather of a kosher turkey.

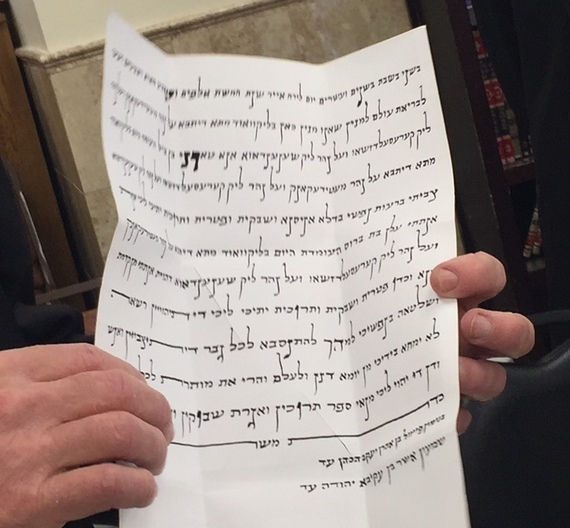

There's great symbolism in this ceremony. The word "get" is comprised of two Hebrew letters, the gimel and the tet. The two letters do not appear anywhere else in scripture -- after all, this is about separation and the two are separate except in this instance. In the Hebrew alphabet, each letter has a numerical value. The gimel is three and the tet is nine. Hence: twelve.

Why is that symbolic? Because the get is comprised of twelve lines of text, written (in this case) in Hebrew. It's written in the first person, as if I wrote it myself, and mentions the date, the place where it was written, and the names of Ellen and her father and me and mine. All of this is arranged in twelve perfect lines, a square of text.

The writing is intense. The letters cannot touch -- again, this is about separation. Once the ink is dry -- and it must be dry, lest it spread -- the get is signed.

When my get was ready and dry, its validity was discussed among the scholars, and I was asked a few more questions.

Having been written, witnessed, and approved, now the get needed to be presented by me to Ellen. You guessed it: more ritual. We stood, facing each other, her hands cupped before her. The rabbi folded the get and handed it to me. I was prompted to recite several lines in English and Hebrew, then dropped the get into her hands. It had to be dropped, not placed. Maybe this is to assure that we are not touching the get at the same moment. Ellen tucked it under her left arm, to be near her heart, and walked several feet away, symbolizing her being apart from me, and then the get was sliced with a knife. I imagine this is to symbolize the death of the marriage, much in the way that observant Jews rend clothing when someone dies.

Believe me, the DMV for Jewish divorce this isn't.

What surprised me was the ceremony's emotional weight. Its gravitas. Eighteen months ago, Ellen and I divorced collaboratively. We did not need to appear together in court. Though emotional, our civil divorce was, well, civil. The getting of the get, while no more difficult in the practical sense, was harder on my heart. It felt much more... final. It felt like a divorce before God, far more meaningful than a sheaf of papers presented to a judge in New Jersey. When I told Ellen, in Hebrew and in English, that I released her and that she was free to move on with her life without me, I was unexpectedly moved.

Driving up to Lakewood, Ellen and I riffed on the word "get." "We're off to get a get." "It's getting late. We better get going." "We're going up to Lakewood. Can we get you anything?" We did that to lighten the mood, because in the end the get is serious business. It's tradition. It's meaningful. For two people who are more culturally and spiritually Jewish than Jewish in the religious sense, the get brought us an oddly calming sense of having, well, gotten to a new place.