Steve Mass, the Mudd Club, Wagner and Me

by Lawrence D. Mass

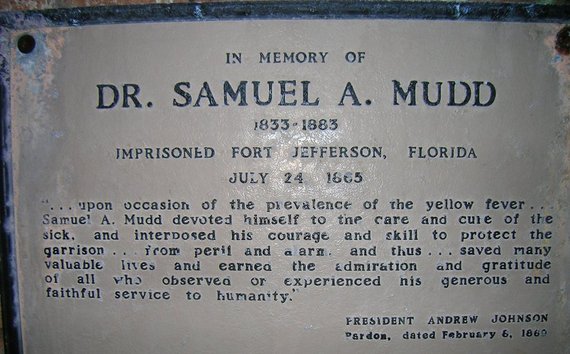

For those who've wondered about the origins of Steve Mass's embracement of Dr. Samuel Mudd, a distant relative of news anchor Rodger Mudd and a staunch confederate who was convicted of conspiracy in the murder of Lincoln but later pardoned, Steve himself has acknowledged that the name was little more than an affectation without any intended meaning beyond the name's catchiness.

Even so, one can't help pondering associations. Steve, like Mudd, was born and bred in the South. When he agreed to treat John Wilkes Booth, the wounded assassin of Lincoln, where should Mudd's loyalties have been--as a physician, rebel or law-abiding citizen? Where should Steve's loyalties have been when he was growing up--as a Southerner, as a Jew, or as his own independent self? Later, when he came of age, should he have chosen to be a responsible wage-earner or free-spirit entrepreneur? Having made the choice to become a club impresario, what should Steve's priorities have been as he attempted to cultivate and showcase writers, artists and musicians, many of them unknowns and many of whose needs could be peculiar, clandestine, demanding and illicit? As he simultaneously struggled to create and lead a tribe and fashion an image of himself, to promote and manage his club, to stay afloat financially and wrestle with his own personal demons, what were the standards and values to be? Like Mudd's place in the orbit of Lincoln's assassination, Steve's place in the club scene swirl of arts, culture, sex, drugs and money remains open to speculation.

Pardon of Dr. Samuel Mudd by President Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Lincoln and was later impeached

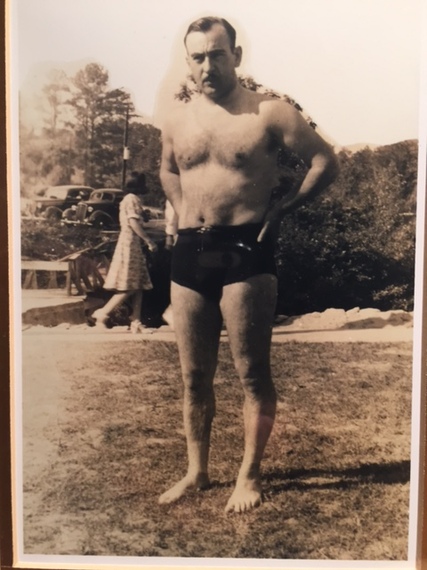

Another doubtless unintended association with Dr. Mudd may have been an awareness of our Dad's role as a pathologist and medical examiner in a time and place of segregation, when and where racist crimes of omission as well as commission were common. In Macon, and throughout the South, segregation was total. Separate bathrooms, schools, entrances, water fountains. The bus I took to go downtown had a sign up front that read: "White people seat from front. Colored people seat from rear."

Though Dr. Mudd's place in the assassination of the President was never clarified, he came from a family of slave-owners and was known to have hated Lincoln. Though our Dad never evinced any racism that we were witness to, he performed his medical duties, never otherwise directly addressing the politics or social circumstances surrounding them, at least so far as we ever knew. We were children, of course, but not so unlike his Jewish family's tacit complicity in the status quo racism of the South that Tony Kushner exposes in Caroline or Change, our family's responses to the pervasive racism in the South that is likewise the subject of the Kathryn Stockett novel and film, The Help, were hardly in the forefront of social activism, which scarcely existed in those years in any case. In fact, apart from my mother forbidding us ever to use the word "nigger" that everybody used at school and most everywhere else in Macon, except in the Temple and Schul, I don't remember Mom or Dad ever really discussing the still festering racism of the South that otherwise felt like home to us, the only home we kids had ever known.

Such was the depth of that Stephen Foster and Ray Charles sense of home that when I learned we were to move to Chicago in 1958, when I was 11 and Steve was 17, I cried. We retained our home in Georgia for another 50 years. To this day, I still experience a heartfelt comfort in the South and in the presence of Southerners that can only be described as primal. As with my initial heimat love of Wagner, no matter how far down the road I've traveled, my heart still sometimes longs for the old folks at home, even as my head knows I can never go home again.

Nor did our parents ever discuss the other behemoth in our living room, the Holocaust, the worst of which was unfolding during Steve's childhood. It wasn't until I was 12, in Chicago, that my mother first said something in my presence about Hitler having murdered millions of Jews. While it may have registered for the future, at that young age of assimilationist youth, of trying to be as un-Jewish, as "cosmopolitan," as "American" and "normal" as I could get away with while otherwise getting bar-mitzvah'd and socializing in a predominantly white middle-class Jewish milieu, I had no questions or interest in hearing anything more about what had happened to those people, old people from history, old Jews in Europe, not real living modern people like us. Such was this disconnect during those years of deeply internalizing anti-Semitism that when I got to know our East German cousins, who survived the Holocaust as kindertransportees--and whose close friend was Szymon Goldberg, the first violinist of the Berlin Philharmonic who likewise fled Nazi Germany never to return--it still didn't occur to us kids that their relatives were our relatives, and that they were not just "those people," but us.

Meanwhile, I don't remember anyone in our family, including our relatives in Chicago, or anyone at Temple or Schul discussing or even mentioning the Holocaust during the years of our upbringing in Georgia. Periodically, though, my parents spoke Yiddish, which they both grew up with and which I did not understand, apart from a few words. Steve doubtless knew more. Could it be that some of their "crazy Jew talk," as my sister once referred to it and I myself tended to think of it, were times when they spoke of what happened in Europe?

Around the time my clearly dismayed father caught me trying on a pleated lamp shade as a kind of ballet skirt (I must have been 5), adolescent Steve was invited to join Dad and several of Dad's golfing buddies and their sons on a fishing trip off the Georgia coast. I remember my mother saying something about one of the best-known of the resorts there being "restricted," the term that was used for No Jews Allowed. Dad was an outstanding golfer and I recall some issues around the best golf courses there and their policies of restriction, issues I recalled a short time later when we were among the first Jews to be invited to join the beautiful Idle Hour Golf and Country Club in Macon.

Although I had no real interest in fishing or golf (my big sports interest was swimming), I was jealous that Steve, as the older brother, got to go on that Sea Island jaunt and I didn't. Steve, meanwhile, had his own jealousy of me as the younger brother now displacing so much of his family's time, attention and affection. Although I never experienced any of the primal Cain-and-Abel physical violence that can erupt in these circumstances of rivalry among siblings, of the older chick trying to push the younger one out of the nest, one incident stayed with me.

At age 5 or so, I acquired a little plastic change holder, a toy version of the metal ones our bus drivers wore on their belts, a gift from my uncle in Chicago who managed a convenience store or from the Macon toy store owned by the Kaufmans, one of the town's oldest Jewish families. (Marian Kaufman, the matriarch and a Weslyan graduate, compiled a history of the Jews of Macon.) Press the various levers and the change holder would dispense quarters, nickels, dimes and pennies. Steve was jealous and after first threatening to destroy it if I didn't stop goading him, he grabbed this favorite toy from me, threw it on the floor and stomped on it as hard as he could and repeatedly, breaking it into many little pieces. I remember crying.

Whatever the incidents, rivalries and other challenges, Dad, a stern disciplinarian, didn't seem partial to any one of his children. Later, I would learn that he was a closet journalist who eventually gave up his writing--except for medical publishing and writing and illustrating children's stories in letters to nephews and nieces--to more fully embrace his calling of medicine. Beyond his gift for literary expression and illustration, he was a skilled visual artist who continued to paint and create even after losing fingers from the skin cancers that were a high risk of the radiologists of his era who handled Cobalt 60 and other radioactive materials in early efforts to treat cancer patients. A heavy smoker, Dad died from cancer of the pancreas at the young age of 63. Whether that cancer was likewise a consequence of radiation exposure we will never know.

Beyond a polymathic creativity, there was another of Dad's traits that Steve and I shared. Moreso than our similarly creative sister, and notwithstanding our skills at getting on well with people, the Mass men harbored a notable distrust of humanity, a weltanschauung of humankind as prone to relentless and endless aggression, marauding, plundering and pillaging, which is how Dad characterized history in the journal fragments he left behind. While my sister ardently believed in the promise of progressivism and socialism, Steve and I, like our Dad, and though far from uncaring, were a lot more skeptical of humankind's potential to transcend its baser inclinations.

In his last years, Dad became my close friend, to the extent that he was the first relative I came out to. Responding to my inquiry, Dad didn't recall any homosexual inclinations he had ever had as a young amateur boxer and wrestler, and he did express his concern that in professional and social circles I'd be "found out." This was 1969, the year of the Stonewall uprising that sparked the modern Gay Liberation Movement in America, but which was still 4 years prior to the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association. In those days, laws against homosexuality were still universal and there were no civil liberties protections anywhere. Being openly gay was still limited to a handful of very brave activists, like my life partner Arnie Kantrowitz, who I wasn't to meet for another decade. Coming out as I did to my Dad was still highly unusual. A distinguished physician and mammography pioneer who specialized first in pathology and later in radiology and after whom they named the Macon Hospital library the Max Mass Library, Dr. Max Mass died 2 weeks before I was accepted to medical school.

By contrast, and though I later came out to him without any discomfort, such was the distance between Steve and me that he was not one I would seek out very often to confide in. The problem was never any level of prejudice or judgment on Steve's part so much as an absence of any genuine or reliable relationship with him, some of this perhaps attributable to his being 6 years older than me. While this failure of bonding might seem a source of enduring enmity, it didn't seem personal because even in those early years of growing up Steve's self-absorption, his remoteness, his closed-offness to intimacy, his reclusiveness, his secrecy, seemed global.

Though Steve seemed to know everybody, the only sustained relationship I ever knew him to have had was with an ex-girlfriend, the writer and anthology editor Helen Mitsios, whose collections of Japanese and Icelandic fiction have been praised and who co-authored with her mother a bracing memoir, Waltzing With The Enemy.

Waltzing is the story, in her own words, of Rasia Kliot's (Helen's mother) experience of Holocaust survival, and likewise in her own words, of Helen's story of her own coming of age and awareness. The book is divided into two parts, Rasia's Story and Helen's Story. Hiding her Jewishness was the great secret that her mother had kept, so tightly that not even Helen, who she raised as Catholic, knew of it during her own childhood.

Helen's loyalty to Steve sustained itself, even as he moved to Berlin and she went on to marry another, architect and landscape artist Tony Winters. Was Helen's enduring relationship with Steve best explained by attraction, codependence, genuine friendship, because of his connections and intersections with the worlds of writers and artists, or a deep empathy that withstood and transcended the not-thereness from which so many of those who knew Steve eventually detached?

As described by Helen in Waltzing,

"Like my mother, [Steve] kept the fact that he was Jewish a secret. Like [her], he had a totally different private and public persona. He didn't trust people and assumed everyone was out to take advantage of him...[he] had little faith in human nature. However, in public, his persona was completely different. He was gregarious and an iconoclast, so stylishly oblivious with his beard and plaid flannel shirts that he became the very essence of hip."

In the film, Driving Miss Daisy, Patti Lupone plays the 1950's daughter-in-law who, dressed in red-and-green plaids, overdoes Christmas as her way of blending in, just as Miss Daisy (Jessica Tandy) would likewise defuse the surrounding anti-Semitism by being the genteel Southern white lady who, in the wake of the bombing of a local synagogue, must inevitably face her minority kinship with her black chauffeur (Morgan Freeman). Miss Daisy reminded me of our own mother, Mignon Masha Segal Mass Thorpe (after Bill Thorpe of Chester, Pennsylvania, her second husband), who delighted in being called "Mz. [Mays]", a pronunciation that made her feel more Southern. For the Mass family children, the drive to assimilate was to take alternate routes. For me, there was opera, Wagner and gay life. For my sister, progressive politics and environmentalism. And for my brother, the enterprise of creativity.

Recently, after all those years of estrangement and as facilitated by Helen, Steve, Helen and I had a reunion. Looking remarkably youthful and healthy at 75, ever-observant Steve, on a visit from Berlin where he still resides, had trenchant observations about Germany today. It seems obvious to him that there is no longer any real controversy about Wagner's preeminent and surpassing esteem in German history and culture. Perhaps the most important and influential of those contemporary Wagner lovers and defenders cited by Alex Ross, Chancellor Angela Merkel is a bellwether of Wagner's current place in Germany. So much so that even Steve--whose milieu was pop culture but who majored in philosophy with an emphasis on such German heavies as Marx, Engels, Hegel and Jaspers, and who was once something of a Wagnerite himself--couldn't help but take note of it.

Yes, Germany and Bayreuth have done much to distance themselves from the past. So has the American South. But scratch the surface, as Donald Trump has done, and the old prejudices, values and racial loyalties are right there. Though Mrs. Merkel has been scrupulous in distancing herself from overt xenophobes, racists and anti-Semites, and welcoming to immigrants, her championing of Wagner, even with articulate qualifiers, arouses concern in a time of far-right resurgences. When I first became aware of her Wagnerism, I found it troubling. In my fantasies of change in postwar Germany, I somehow imagined that a figure like Merkel, even if she shared a nearly universal appreciation of Wagner as composer and artist, might, as Chancellor, want to keep her distance from the citadel of Hitler's Reich that was Bayreuth; but that, as it turns out, was wishful thinking.

Clearly, Helen Mitsios gleaned in Steve Mass some of the same deep wounds, secrecies and honed instincts of survival, and specifically Jewish survival, that were hallmarks of her mother's story. But is her perception of Steve as a kind of survivor and indirect, impassive victim of the Holocaust fully explanatory? Or are the keys to a broader understanding likely to be found as well in other contexts and viewpoints, such as the Japanese literature and sensibility Mitsios, who edited the NYT editor's choice anthology, New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, has otherwise shown such an affinity for? Indeed, the story of Steve Mass, which he himself is now endeavoring to write, may be more redolent of the legendary Japanese tale of Roshomon, originally from a medieval Noh play and eventually a Kurosawa film classic.

As we finished our pleasant mid-afternoon get-together over coffee and pastry at Greenwich Village's Marlton Arms Hotel, Steve, Helen and I took our leaves cordially. Helen and I embraced. When I turned to embrace Steve, my open arms were met with a two-handed handshake that was at once warm and distancing. When he and I had dinner a few nights later at the Knickerbocker, with its large collection of Hirschfeld portraits of celebrities, neither of us initiated an embrace or handshake, despite the apparent good will on both our parts. Steve had to cut the dinner short, rushing off, as he was always wont to do, this time to catch what he said was the last train to his suburban hosts. The following week I got an email from him that was signed "Warm Regards." It was not only the warmest but also the only written expression of well wishes I can recall ever having received from my brother.

to be continued