Six years ago we paid about $700 for a new KitchenAid dishwasher. Since then, we've spent considerably more than that getting it repaired. Each repairman (and they've all been men) who came to our house told us the same thing: most of today's appliances are junk. Both the workmanship and the parts are not made to last. They are designed to break down so consumers have to keep buying new ones, make expensive repairs, or buy costly extended warranties.

When we originally purchased the dishwasher we didn't buy additional insurance beyond the one-year warranty that comes with the appliance, which is why we've poured so much money into it as it keeps breaking down. We thought that extra warranties were a rip-off. So, instead, we kept hoping that each repair would be the last, and each time we were wrong. It cost about $150 each time a technician comes to the house. Then there are additional costs for labor and parts -- like a few hundred dollars to replace a rubber rack whose wheels kept breaking.

Last month the damn machine wouldn't even start, so a Sears technician came to our house and fixed the problem -- a broken fuse. Finally, this week -- when the dishwater again wouldn't start -- the Sears repairman who came to fix it (by replacing the fuse, again) persuaded us to buy a five-year warranty that cost about $500. He said it was smarter to buy the warranty than to buy a new dishwasher, because the new ones are more fragile than the older ones.

In essence, the five-year warranty --which Sears calls our "master protection agreement" -- requires consumers to pay almost double for major appliances. First you buy the appliance, then you purchase the extended warranty, which cost almost as much as the machine. They sucker us into this arrangement because we know that most appliances are not built to last, but to break down. Indeed, the Sears repairman offered to sell us additional warranties for our refrigerator, washing machine and dryer, air conditioner, and hot water heater. Economists used to call these products "durable goods," but that term now seems so out of date.

In retrospect, we should have purchased the extended warranty when we originally bought the appliance. Now we've done it. It is never too late to learn.

But what, exactly, have we learned?

This isn't a problem limited to dishwashers (66% of U.S. homes have one) or to KitchenAid or Sears products. It is deeply ingrained in how capitalism -- or at least American-style hyper-capitalism -- works.

Today's appliances -- like many consumer products -- are built to break. It is not a matter of consumers mistreating their products. It is designed to maximize corporate profits. This is a concept called "planned obsolescence."

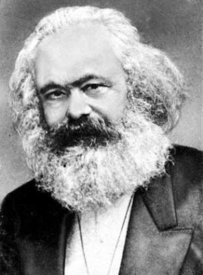

I'd always associated the term with the late John Kenneth Galbraith, the brilliant Harvard economist whose 1958 book, The Affluent Society, warned that an increasing share of America's economy was devoted to making ineffective products and promoting wasteful consumer spending. He explained that companies manufacture our "wants" through advertising, design new models of things each year that we need in order to "keep up with the Joneses," and, even if we don't get seduced by this year's new model, make us keep buying new products because they are designed to fall apart.

It turns out that The Affluent Society helped popularize these ideas, but, in fact, Galbraith didn't coin the term "planned obsolescence."

Some trace the origins of the phrase to Bernard London's 1932 pamphlet "Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence." Writing in the middle of the Great Depression, London believed that the government should place a legal time-limit on the use of consumer goods in order to increase consumption and stimulate the economy. We've typically identified this idea with the automobile industry, and for good reason. In the 1930s, General Motors CEO Alfred P. Sloan Jr. came up with the idea of annual model-year design changes to persuade car owners that they had to buy a new replacement each year. Sloan called this "dynamic obsolescence."

The phrase "planned obsolescence" gained popularity after an American industrial designer, Brooks Stevens, gave a talk with that title at an advertising conference in Minneapolis in 1954. It was during the beginning of the post-World War 2 prosperity, brought about primarily by federal government spending -- huge public investments in roads and highways, homebuilding (thanks to government-subsidized mortgages), higher education (through government-backed financial aid and expansion of university enrollment), and Cold War military spending. But for that prosperity to continue, consumers had to keep consuming more and more. As Stevens explained in his speech, planned obsolescence was "instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary."

America's postwar prosperity -- suburbanization, home ownership, and new household goods like vacuum cleaners and freezers -- was gaining momentum when The Affluent Society came out. Galbraith was impressed with America's technological capacity to produce things, but he said that rising gross domestic product was not the best measure of a society's well-being.

Galbraith warned that America was investing too little on public needs -- education, infrastructure, parks, scientific research to prevent diseases, health care, job training, the arts, and safety net provisions for the poor. Big corporations could move quickly to invent and produce new products and whet consumers' appetites, but democratic government was unable to move as rapidly to raise taxes and invest in public programs. America's priorities were out of whack, Galbraith wrote. For example, if auto companies build more cars, government needs to invest more money on public roads and places to park. Americans have lots of vacuum cleaners in their homes, but governments have too few street-cleaning machines.

Echoing Stevens' observations - but with a different sense of capitalist morality and ethics -- Galbraith noted that corporations had to manipulate consumers, through advertising and market research, to feel unsatisfied with their existing standard of living and to demand things they did not have or did not need. As a result, America was overloaded with useless products. Big business could persuade consumers that the next version of each product -- cars, toasters, refrigerators, toys, clothes, televisions -- was bigger, better, and absolutely necessary. Companies designed major and expensive consumer goods, including cars, to last only a few years before falling apart in order to stimulate demand. Companies also encouraged consumers to "buy now, pay later," leading many of them to overextend themselves -- a trend that led to the explosion of credit cards and massive consumer debt.

Galbraith wrote The Affluent Society more than a decade before the emergence of the environmental movement (the first Earth Day was in 1970), but he was prescient. Today we understand that much of what is produced in the U.S. and elsewhere (particularly our over-reliance oil-dependent plastic products, including many of the parts in my washing machine) is wasteful, destined to wind up in landfills, and harmful to the environment and public health. We talk more and more about the importance of "sustainability" in the way we produce our products and design our cities. Many Americans have become more skeptical about buying gas-guzzling cars or buying a new vehicle just because of a new model change. We kept driving our 2002 Nissan Altima for 14 years, but over that period we probably spent $20,000 in repairs, most of it due to mechanical problems and problem parts, not human-made accidents. We replaced it with a new Toyota Camry hybrid, which, according to Consumer Reports, has a good repair record and is fuel efficient. We'll see.

Of course, despite this new environmental spirit and concern for household budgets, many Americans still feel compelled to buy the most recent edition of cell phones, computers, and other high-tech products, or the next fashion trend in clothes.

But even those consumers who try to avoid wasteful spending can't defend themselves against the ongoing onslaught of poorly-made products and the debt-driving monster called the warranty.

For the next few months, perhaps even a year, we'll wash our plates and glasses in our newly-repaired dishwasher. Then, thanks to planned obsolescence, something will break. We'll call Sears and then welcome another repairman into our home.

What will we do when the five-year warranty runs out? I can't plan that far in advance.

Peter Dreier is a professor of politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College in Los Angeles. His most recent book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books).